[K:NWTS 23/1 (May 2008) 28-46]

The prophecies of Haggai have been recorded for us in the Bible. That may be a surprise to many pastors and scholars, for Haggai is easily overlooked. Nestled between two other obscure prophets with even more obscure names (Zephaniah and Zechariah), Haggai�s prophecy appears to have been lost in the apocalyptic wilderness of the post-exilic minor prophets. It is not hard to understand why. We live in the age of the Crystal Cathedral�in a day when huge sports arenas are turned into magnificent, 30,000-seat worship centers with state of the art sound and light systems. To such a mentality, Haggai can be nothing but a miserable failure. The pagan worship centers of the sixth century B.C. undoubtedly boasted much more glorious appearances than the rearranged pile of rubble once known as the Temple of Jerusalem. How could Haggai expect to attract more exiles from Babylon when the Jews�s place of worship lay in unsightly ruins?� Surely post-exilic church growth suffered a death blow through Haggai�s ministry! What possible relevance, therefore, could Haggai�s person and ministry have for our own contemporary situation?��

Indeed, Haggai�s message is neglected in our day, even as the Lord�s commandment to build the temple was in his own (Hag. 1:1-11). But however obscure and neglected Haggai�s prophecy may be today, his message continues to have nothing less than cataclysmic relevance (Hag. 2:6, 21). All the nations of the earth, yea, even the heavens will tremble at God�s theophanic presence. Though Haggai and his Israelite brothers find themselves in an age of discouragement, Haggai prophecies for them an age of abiding encouragement.� Though the Temple appears to be permanent in its destruction, Haggai prophecies an age when it will be gloriously completed by means of eschatological construction. Haggai, riding upon the wings of the Spirit, flies with his fellow believing Israelites beyond the inglorious ugliness of the present temple, to the eternal glory of the latter temple.

This prophet�s involvement in the careful rebuilding of Israel�s temple appears to have had a profound effect upon him. Even as the bricklayers and masons carefully crafted the temple�s materials into a beautiful structure, so also the prophet has carefully crafted his prophecy by means of an artistic literary arrangement. The same Spirit who gifted Bezalel and Oholiab with artistic skill and ability to build the tabernacle in the first Exodus now carries Haggai along�not only in the proclamation, but also in the orderly inscripturation of the hw��hy>-rb;d. (word of the Lord).[1]�

Anyone who has attempted a remodel knows the necessity of a thorough knowledge of a building�s blueprints. While not always the most exciting kind of reading, architectural plans are crucial for understanding the basic layout of a building. The same is true of Haggai�s prophecy. As we shall see, Haggai�s prophesy evidences a carefully crafted literary and rhetorical structure that reinforces the theological content of his message.

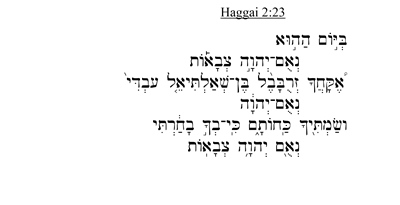

It is widely agreed that Haggai�s prophesy is structured around four chronologically arranged dates (Hag. 1:1; 2:1; 2:10; 2:20). Each of these

dates is accompanied with the revelatory preface: aybi�N�h; yG:�x;-dy:B. hw��hy>-rb;d>.[2] Though other dates occur in the prophecy (Hag. 1:15), they lack this fairly uniform revelatory preface. The fourfold revelatory preface and date clearly suggest a fourfold macrostructure for Haggai�s prophecy.[3] So far our four-part structure looks like this:

A further ABA′B′ parallel arrangement of these four parts is suggested by the following elements. [4]� Let us examine the common elements in the AA′ section. First, each of these oracles are given a full date, while those in BB′ are abbreviated. Second, in the AA′ oracles the prophet makes allegations against �this people� (1:2; 2:14), a phrase that is absent from BB′. Third, the AA′ oracles each deal with economic distress�either drought (1:10-11) or blight, mildew, and hail (2:17, 19). In each instance, the result for the people is hard work with very little yield (1:6; 2:15). Fourth, in the AA′ oracles, the cause of this distress is the failure of the people to rebuild the temple (1:4, 8-11; 2:18-19). Fifth, each AA′ oracle uses the similar phrases ~k,(yker>D;-l[; ~k,�b.b;l. Wmyfi� (1:5, 7) and ~k,�b.b;l. an��-Wmyfi (2:15, 18).� Sixth, the parallelism between the AA′ oracles is chiastically reinforced by reversing the order of the dates. In the A section, the order is day-month-year (1:1), while in A′ the order reverses to year-month-day (2:10). Finally, each AA′ section is bracketed by an inclusio repetition of dates (1:1, 15; 2:10, 18). The parallel between the first and third oracles is clearly established by means of duplicated vocabulary, phrases, and themes, and is stylistically reinforced through the chiastic reversal of dates.

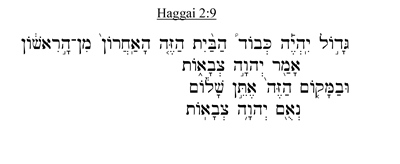

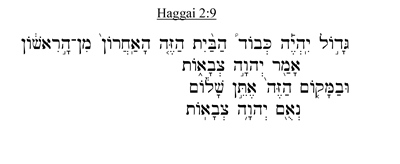

When we examine the second and fourth oracles (BB′), a similar parallelism appears. First, the second and fourth oracles close with the phrase tAa)b�c. hw��hy> ~au�n> (2:9; 2:23), while the first and third do not. In addition to this phraseological duplication, the rhetorical structure of each conclusion is strikingly parallel:

Each promise of exaltation is concluded with the phrase hw��hy> ~au�n> or hw��hy> rm:�a�. In all but one instance the divine name hw��hy> appears in the expanded form tAa)b�c. hw��hy>. Thirdly, in each of the BB′ oracles, the prophet deals with the problem of lowly status. In the second, the focus is upon the lackluster glory of the newly rebuilt temple (2:3). In the fourth, Zerubbabel�s lower status is highlighted in comparison to the kings of the surrounding nations (2:21-23). Each of these oracles also speak of a transition from this lowly condition through an eschatological upheaval (2:7, 9; 2:23). In fact, each contains a clear duplicate reference to the final, cataclysmic �shaking� of the heavens and the earth (2:6 � #r,a��h�-ta,w> ~yIm:�V�h;-ta, �vy[ir>m; ynI�a]w>).

We might chart the evidence supporting the ABA′B′ arrangement of Haggai�s prophecy as follows:

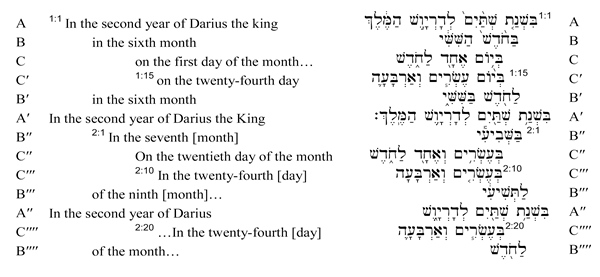

A further note must be added concerning the structural significance of the dates in Haggai�s prophecy. When we examine the temporal headings to each of the four sections, a clear concentric pattern begins to emerge that appears to reinforce our four part ABA′B′ arrangement [5]:

From 1:1-2:10, the first three headings are clearly arranged in a concentric pattern. The first concentric series (1:1, 15) duplicates itself almost exactly, giving a full description of each element of the date. [6] In 2:1, 10, the same concentric pattern of year-month-day-day-month-year continues, though some specific elements begin to drop out. [7] Furthermore, in 2:1, 10, the numerical balance characteristic of 1:1, 15 disappears.[8] However, in the final pericope, the pattern seems to dissolve. In fact, a gradual dissolution of the pattern can be discerned, which is illustrated in the following table:

| Concentric pattern to dates | Darius mentioned | Full Dates | Darius described as �king� | Full Dates with full description | Concentric inclusio delimiting section | Numerical balance in concentric parallelism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1, 15 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2:1 | X | ||||||

| 2:10 | X | X | X | ||||

| 2:20 |

As the prophet moves from A (1:1-15) to A′′ (2:10-19) more than half the common elements drop out: the concentric parallelism begins to gradually unravel. When we come to the B (2:1-9) and B′ (2:20-23), the concentric pattern breaks down completely. Not only does the concentric date-pattern fall out of synch, but the revelatory preface �the word of the Lord came�by the hand of Haggai� precedes the date, in contrast to 1:1; 2:1; 2:10, where the revelatory preface follows it.� All that these two sections share in common is the mere date of the prophecy. Has the otherwise careful literary hand of Haggai the prophet slipped up here, or is there a deeper purpose behind this literary arrangement?

In order to answer that question, we must first briefly note that Haggai�s dates differ dramatically from those of the earlier prophets. Other prophets who provided dates for their prophecies (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Hosea, Amos, Micah, and Zephaniah) did so with reference to the reign of the kings of Judah and Israel. Haggai (and Zechariah, his contemporary) date their prophecies in terms of the regnal years of the Persian king, Darius. The shift in temporal markers is clearly indicative of a redemptive-historical shift from the era of the Monarchy to the era of the Exile. Even returned Israel is not yet fully delivered from her exile! She is still defined by the regnal year of the Persian kings!

Secondly, the progressive dissolution of Haggai�s dating-pattern also seems indicative of another redemptive-historical shift. The prophesy begins with the regnal years of Darius the king chiastically bracketing the entire chapter. Even as Israel is surrounded by the rule of the Persians, so also the first chapter of Haggai�s prophesy is surrounded by Darius. Darius defines and delimits Israel�s present history in chapter 1. However, when we move to chapter 2:1-9, Darius� temporal bracket begins to break down. In the chapter in which Haggai begins his eschatological projection of Israel�s glorious future, no mention is made of the regnal year of King Darius. The eschatological future of Israel transcends and surpasses Israel�s temporal dilemma. As the light of the new age breaks forth upon Israel, Darius�s dominance diminishes�he isn�t even mentioned!� However in 2:10, Darius�s name returns as Haggai highlights Israel�s present uncleanness. However, Darius does not occupy the comprehensive position he did in chapter 1. Moreover, he is no longer described as %l,M,(h; as he was in 1:1, 15. The ending of 2:10-19 does not remind us of Darius�s present reign, but rather the hope of future blessing (2:19). Finally, in 2:20, �time is out of joint�: the chiastic pattern is broken completely. Darius isn�t even mentioned. In his place is a twofold reference to Zerubbabel, governor of Judah/my servant. In contrast to chapter 1 (where Darius�s regnal year served as the literary bracket), Zerubbabel brackets the entire final pericope (2:21a, 23b). In Darius� place stands another ruler�Zerubbabel, governor of Judah, servant of the Lord�whom God will make his own signet ring. There will be no more rule of Darius the Persian in the eschatological age!� God will overthrow him and his kingdom when he eschatologically shakes the heavens and the earth (2:21b-22).

To bring our discussion back to our broader macrostructure, Haggai�s dates not only reinforce our ABA′B′ structural proposal, but also reinforce the theological significance of that structure. In the A section, Darius brackets Israel (1:1, 15). In the A′ section, Darius is mentioned, but has begun to lose his prominence (2:10). But in the B (2:1) and B′ (2:20) sections of eschatological projection, Darius is nowhere to be found! Hence Haggai�s dates are not only structural markers, but a literary device reflective of the redemptive-historical progression of Israel�s hope of freedom from temporal exilic slavery in the eschatological future. Their progressively unraveling concentric pattern points us to the eschatological thrust of Haggai�s prophesy. Israel is moving from temporal crisis (1:1-15; 2:10-19) to eschatological renewal (2:1-9, 20-23); from the temporal reign of Darius the king (1:1, 15) to the eschatological reign of the Messianic servant of the Lord prefigured in Zerubbabel (2:10, 21, 23).

Far from evidencing the hand of a clumsy editor who mindlessly pasted together isolated prophetic units, this macrostructure beautifully reveals the magnificent literary genius of the inspired prophet. Drawing upon a multitude of rhetorical and literary devices and techniques, Haggai presents us with a tightly concatenated oracle of prophetic and artistic literary splendor.�

Having established the broad contours of Haggai�s superstructure, we now turn our attention specifically to Haggai 2:1-9. As we have seen in our study above, each B section is marked by the revelation of a cataclysmic eschatological upheaval in which the distress of the previous section finds its ultimate resolution. In the first AB section (1:1-15; 2:1-9), the distress is centered upon Israel�s failure to rebuild the temple. Having responded positively to Haggai�s initial prophetic discourse, the people now find themselves disappointed and dismayed over the lackluster character of their work. Haggai brings the word of the Lord to encourage them�a word that climaxes in the prophetic projection of an eschatological upheaval which will result in the construction of a temple far more glorious than they could have ever imagined!

Even as Haggai�s prophesy as a whole evidences an artfully crafted macrostructure, so Haggai 2:1-9 demonstrates a carefully arranged rhetorical microstructure. The first half of Haggai�s third oracle (2:1-4) is dominated by a series of �threes.� We begin with a threefold imperative directed to the king, priests, and people of Israel (2:2�note the repetitive la,). This is followed by three rhetorical questions about the former splendor of the temple (2:3�marked by a threefold interrogative: ymi, hm��W, and aAl�h]). In verses 4-5 we have a threefold address to the threefold group, which is marked by the �strong� threefold repetition of an imperative (qz:�x�). When we add up the subunits, we are left with a total number (surprise!) of three! The threefold ternary pattern literally jumps off the revelatory page! The following arrangement of these verses in English makes this very clear:

������ Speak now

��������������� (1) to Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah,

��������������� (2) and to Joshua the son of Jehozadak, the high priest,

��������������� (3) and to the remnant of the people saying,

��������������� (1) Who is left among you who saw this temple in its former glory?

��������������� (2) And how do you see it now?

��������������� (3) Does it not seem to you like nothing in comparison?

��������������� (1) �But now take courage, Zerubbabel,� declares the Lord,

��������������� (2) �take courage also, Joshua son of Jehozadak, the high priest,

��������������� (3) and all you people of the land take courage,� declares the Lord [9]

In addition to the general threefold pattern of Haggai 2:2-3, we also note the concentric orientation of the prophet�s rhetorical arrangement. This concentric orientation is most clearly seen in the way the prophet �sandwiches� the three rhetorical questions in verse 3 between the threefold mention of Zerubbabel, Jehozadak, and the people in verses 2 and 4. The prophet is artistically drawing our attention to the central focus of this oracle: the inglorious condition of the present temple. In addition, it is possible that these verses are organized in a more complex concentric arrangement [10]:

������ Zerubbabel�governor of the land of Judah (2:2a)

��������������� Joshua son of Jehozadek the high priest (2:2b)

��������������� ������ Remnant of people�no description (2:2c)

������������������������������� Question: comparison of former and latter temples (2:3a)<

����������������������������������������������� Question: disappointment of the now (2:3b)

������������������������������� Question: comparison of former and latter temples (2:3c)

��������������� ������� Zerubbabel�no description (2:4a)

��������������� Joshua son of Jehozadek the high priest (2:4b)

������ People of the land (2:4c)

The purpose of such an organization is not difficult to see. By means of the concentric arrangement the reader is pressed down into the central concern of the governor, priest, and people: the present (hT'�[) dilemma of the inglorious temple. In other words, Israel is faced with the dilemma of an apparently unrealized eschatology! The present temple, whose glory was expected to far surpass that of the former, now appears as nothing in their eyes. Israel�s focus is on the visible and the seen. Notice the repetition of visual/optical terminology in 2:3: ~k,(ynEy[eB., ~yai�ro,�ha�r�. While Israel�s discouragement flows out of her focus on the visible, God�s prophetic encouragement will come through directing them to the invisible: the Exodus-Spirit abiding in their midst, and the eschatological cataclysm to come.�

When we come to verses 2:4bff, there is an apparent break in the previously established threefold pattern. The transition from 4 to 5 at first seems so difficult that some have argued that it is obvious evidence of editorial interpolation. [11] However, close analysis of the text reveals the same kind of nuanced patterning present in verses 1-4.

Haggai 2:4 contains two occurrences of the phrase hw��hy>-~aun>. Some critics have argued that this is a clumsy arrangement, but it actually serves two important literary purposes: (1) to clearly delimit 2:4 as a subunit; (2) to draw the reader�s attention to the priest-figure of Joshua, Son of Jehozodak.[12] We might structure this subunit as follows:

��������������� A � Zerubbabel + hw��hy>-~aun><

������������������������������� B � Joshua the high priest

��������������� A′ � All the people of the land + tAa)b�c. hw��hy> ~au�n>

The high priest is thus enfolded between two explicit revelatory declarations. In a pericope and prophecy that is devoted to the cultic arena (temple), it is not surprising that Haggai chooses to centrally highlight Joshua the priest!� Our apparent editorial klutz turns out to be a structural and literary genius!� The absence of an explicit revelatory declaration with Joshua makes him the structural focus, reinforcing the prophet�s theological focus on the rebuilding of the temple.

Furthermore, the final revelatory declaration (tAa)b�c. hw��hy> ~au�n>) serves as a hook to the final subunit in 2:6-9, which is structured by a recurring repetition of� tAa)b�c. hw��hy> ~au�n> followed by tAa+b�c. hw��hy rm:�a� (2:7c; 2:8b; 2:9b; 2:9d). In other words, Haggai concludes the first half of this section with the structural marker that will dominate the second section, thus tightly binding them together as one holistic unit. Far from evidencing a clumsy editor, Haggai 2 presents the reader/listener with a finely tuned rhetorical and literary structure. Like any good piece of literature (or architecture!), its independent units are unique and distinct, yet are linked by clear structural markers. [13]

Finally, if we take 2:1-2 as an introductory formula, the message proper of 2:3-9 may form a chiasm[14]:

A - 2:3 � Present glory of the temple compared with former glory of the temple (!Av+arIh� Ad�Abk.Bi hZ<�h; tyIB:�h;-ta,)

��������������� B � Israelites, Judah � (2:4)

������������������������������� X � Presence of Glory-Spirit with Israel (2:4c-5)

��������������� B′ � Heavens, earth, all nations, all nations! � 2:5-7

A′ - 2:9 � Present and former glory of the temple compared with the latter glory (!Av�arIh��-!mi �!Arx]a;(h� hZ<�h; tyIB;�h; �dAbK.)

A and A′ provide clear semantic links. Yet they also indicate an expansion, enrichment, and growth.[15] Thus B and B′, though lacking clear lexical connections, may nevertheless be coordinated by means of the expanded chiastic paradigm: Israel, what is more all nations; Land of Judah, what is more the heavens and the earth! The Pneumato-centric hinge of the chiasm (X) is thus the abiding presence of the Spirit amongst God�s people. The central focus on the Spirit�s presence becomes the hinge of the transition reflected in Haggai�s prophesy. 2:5 begins with a retrospective reflection upon the promise of God in the Exodus, moves to a reinforcement of the Spirit�s present presence in Israel (2:5), and finally to an eschatological projection of the Glory-Spirit in the latter temple (2:6-7).

This prophetic projection of the eschatological glory of the final temple comes to a people who have re-experienced the thrill of freedom from bondage. Even as Israel was redeemed from the bondage of Egypt in the former era, she now finds herself in the midst of a new liberation. The reversal of slavery to freedom in the Exodus which had been reversed in the bondage of Babylonian exile has now been reversed once again in the post-exilic returns. Ever since the decree of Cyrus the Great in 538/7 B.C., a group of exiles were experiencing a new exodus�from bondage, from curse, and from sin�even as God had promised in the law (Lev. 26:40-45)[16] and in the early prophets (Is. 43:16ff; Hos. 2:14-15, etc.).

Upon their return, the first order of business was the reconstruction of the temple. In the seventh month, they first built an altar to the Lord and celebrated the Feast of Tabernacles (Ezra 3:1ff). By the second month of the second year, the reconstruction of the temple proper had begun (Ezra 3:8ff). Yet it was becoming evident (particularly to the older Israelites) that there remained something lackluster in this rearranged pile of rubble (Ezra 3:11-13). Indeed, there was something bittersweet about this new exodus�a mixture of joy and weeping (Ezra 3:12).

Yet more was added to this already displeasing mixture�the even bitterer oppression of the surrounding foreign nations (Ezra 4). Having been freed (twice over!) in Exodus-liberation from bondage to foreign oppressors, they appeared to be in bondage all over again to the manipulating �people of the land� who forcibly stopped the work on the new temple. Into this historical context come the prophetic messages of Zechariah and Haggai (Ezra 5:1; 6:14). Not surprisingly, each prophet deals extensively with the building of the temple.

One further note must be added concerning the historical context of Haggai�s prophecy. As previously noted, his oracle comes during the Feast of Tabernacles (Hag 2:1; Lev. 23:34, 36; Num. 29:12).[17] This festival was a great reminder that Israel was always to be a congregation of pilgrims (Lev. 23:43)�sojourning in tabernacle-temples, even as God dwelt among them in the tent in the wilderness. The earth (particularly Canaan) was not their true home. By means of the feast, the Israelites would re-actualize the wilderness-experience in their midst. Though settled in the land, they were people longing for a better country�that is, a heavenly one (Heb. 11:16). They were people longing for a better temple�one not made with hands, established in the heavens. All of their dwelling places on earth, however permanent they may have seemed, were only temporary campsites. The Feast of Tabernacles thus provides a dramatic redemptive-historical backdrop reminding them of the impermanence of all earthly worship centers.

Indeed, as Israel works to build the Lord�s house, constant reminders of impermanence and transience are all around them. Though Israel expected an abiding permanence as she returned from exile, all the provisionality of the former era comes sweeping down upon them. Into this arena of decay and dejection comes the prophecy of Haggai 2:1-9. This existential movement from dejection to prophetic hope is reinforced by the broad ABA′B′ macrostructure of Haggai�s prophecy. As noted above, the A sections set forth the people�s present distress, and the B sections proclaim encouragement through eschatological resolution.

The temple stands at center stage in Haggai�s prophecy as it is couched within a retrospective and prospective redemptive-historical dynamic.[18] Retrospectively, the prophecy reaches back to the first Exodus. The exhortation to be strong and work is grounded (yKi�) in the promise of God in the first

Exodus: �for (yKi�) I am with you�according to the covenant that I made with you when you came out of Egypt� (Hag. 2:4-5). The protological shaking of the earth at Sinai (Hag. 2:6) also provides the retrospective backdrop for Haggai�s projection of Israel�s future possession of the nations. Furthermore, the mention of the �former glory� of the temple (Hag. 2:3, 9) links the prophecy back to the �glory days� of David and Solomon, when the temple�s beauty and splendor were at their height.

All of this is brought to bear upon Israel�s existential present. As she contemplates her faded glory, the prophet addresses himself directly to Israel�s present situation (note the doubled emphasis on hT��[; [�now�] in 2:3, 4). She is directed not only to her glorious past, but also to the semi-eschatological down-payment of the Glory-Spirit (2:5), which is structurally central to Haggai�s prophesy. In other words, as she despairingly compares the glory of the former and present temples, she is directed not only to what Yahweh will do in the future, but also to the present intrusion of that reality in her midst. Even as Israel is beckoned to continue work on the typological temple, she is also invited to look beyond its inglorious condition to the temple of the Glory-Spirit that is already invisibly present within her. Old Testament Israel already has vital contact with the life-giving Spirit of the age to come!

Against this retrospective redemptive-historical background, as well as the dilemma of Israel�s present situation, Haggai prospectively projects Israel�s eschatological future. If Israel was brought out of Egypt in ancient times, in the eschatological age there will be a new exodus in which Israel will be freed from foreign bondage.[19] If David and Solomon built a glorious temple that now lies in ruins and stripped of its treasure, God will build an eschatological temple with treasures from all nations. If God caused the earth to shake at Sinai when the final day intruded upon Israel in the wilderness, so in the final day God will shake not only the earth, but also the heavens in eschatological upheaval (cf. Heb. 12:25-29). [20] If Israel�s present is characterized by strife and battle with the foreign nations, there will come a day when there will be no more battle, but peace�through the bringer of Peace who is to come (Hag. 2:9).

This universalistic emphasis is further reinforced by the chiastic hinge created by the BB′ sections of Haggai�s prophesy (2:4, 5-7). As Haggai�s tripartite address to Israel�s king, priest, and people turns upon the central hinge of the Spirit, the door of redemptive history becomes opened to the nations. Haggai�s literary and rhetorical structure is reflective of the movement of redemptive history�from Israel, to the outpouring of the Spirit, to the inpouring of the nations! The Spirit, whose glory is at the center of the latter age, knows no distinction between Jew and Greek.

Yet not only the Spirit, but particularly the Christ will be found on center stage in this glory-arena. Even as Israel�s king, priest, and people work to build the protological second temple, there will come an eschatologically Spirit-filled king, priest, and people who will work to build the semi-eschatological temple in the fullness of time. Jesus is the eschatological king�son of Zerubbabel (whose name means �seed of Babylon�) and son of the exile (Mt. 1:12-13, 16). Jesus, not Darius, is King of kings in the eschatological age! [21] Jesus-Joshua is the eschatological high priest who ministers in the heavenly temple (Zech. 3; Heb. 4:14-5:10; Heb. 7-9). Jesus is the eschatological people of God, who will inaugurate in himself a new exodus (Mt. 2:13-15; Lk. 9:31). Jesus is the eschatological temple-builder, who will raise up his temple-body three days after it has been destroyed (John 2:18-22).

But it does not stop there. For Jesus comes as the foundation of the eschatological temple (1 Cor. 3:11; Eph. 2:20-22), which will by no means remain bare, empty, and unfinished. Upon the foundation of Jesus is built the temple of the church, which is being made into a dwelling place of God by the Spirit (Eph. 2:25). The apostle Paul was very conscious of his own participation in this temple-building work. Even as the presence of God�s Spirit among the protological temple-builders became the ground for Haggai�s exhortation to work heartily, so also the Spirit�s presence in the semi-eschatological temple becomes the ground for the Paul�s exhortation to the church to be built up through faithful preaching and church discipline (1 Cor. 3:16; 6:19-20).

The apostle Peter also reflects this consciousness of being a participant in God�s work of temple-building. He addresses the church as living stones of a spiritual house to be a holy priesthood to offer spiritual sacrifices to God through Christ (1 Pet. 2:4). This temple is built upon Jesus Christ as the foundation (2:6-8). In Christ Jesus, the eschatological Israel and priest-king, the church too becomes a royal priesthood and a holy nation to proclaim his praises for the new Exodus accomplished in him (2:9-10).

Haggai 2:1-9 proclaims new things to come: a new Exodus, a new Temple, a new return from exile, and a new age in which Christ and the Spirit alone occupy the central place. The apostles were conscious that even as these new things had broken in upon them in the semi-eschatological age, they would also be available to all those in the coming age who would be united to Christ by faith. As the faithful of God survey the apparently barren landscape of the modern Temple-Church and are tempted to shrink back in despair and dejection, they would do well to revisit Haggai�s prophecy of the glory of the latter temple. For that temple is being built now upon the foundation of the collective witness of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone (Eph. 2:20). She may be afflicted, perplexed, persecuted, and struck down, but she will never be crushed, driven to despair, forsaken, or destroyed. Having been made to possess the semi-eschatological indicative of the Spirit�s latter glory through union with Christ, she must heed the semi-eschatological imperative of Haggai to those who await the consummate perfection of God�s glory-temple: �Work, for I am with you, declares the Lord of Hosts, according to the covenant that I made with you when you came out of Egypt. My Spirit remains in your midst. Fear not!� For how can they be afraid?� God will build his temple-church�even the very gates of hell will not prevail against her! She only awaits the consummation of her already inaugurated hope�a hope projected in Haggai, and beautifully portrayed in its fulfillment by the apostle John:

And I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God gives it light, and its lamp is the Lamb. By its light will the nations walk, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it, and its gates will never be shut by day�and there will be no night there. They will bring into it the glory and the honor of the nations. (Revelation 21:21-26, ESV)

BWHEBB, BWHEBL, BWTRANSH [Hebrew]; BWGRKL, BWGRKN, and BWGRKI [Greek] Postscript� Type 1 and TrueTypeT fonts Copyright � 1994-2006 BibleWorks, LLC. All rights reserved. These Biblical Greek and Hebrew fonts are used with permission and are from BibleWorks, software for Biblical exegesis and research. This copyright must be displayed and preserved when distributing this article.

[1] The text suggests an interesting antithesis between the Spirit-borne prophet and the defiled Israelites. Israel�s hands are defiled (2:14), and apart from God�s blessing and grace all of the works of her hands are cursed (2:17).� Into this situation of hopelessness and sin comes the word of the Lord �by the hand of Haggai the Prophet� (1:1, 1:3, 2:1)�an expression that only appears in one other place (Mal. 1:1).�

[2] Only 2:20 lacks aybi�N�h;

[3] Some have suggested a chiastic structure, e.g., M.H. Floyd, Minor Prophets (2000) 257-58.� Baldwin (Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi: And Introduction and Commentary [1972] 35) and Peckham (History and Prophecy: The Development of Late Judean Literary Traditions [1993] 741) suggest a threefold structure.� By contrast, Verhoef separates 1:13-15 from 1:1-12, resulting in a five-part structure (The Books of Haggai and Malachi [1989] 20-25).�

[4] An ABA′B′ structure has been suggested by B.S. Childs (Introduction to the Old Testament as Scripture [1979] 469-70), John Kessler (The Book of Haggai: Prophecy and Society in Early Persian Yehud. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 91 [2002] 250-51), Eugene Merrill (Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi�An Exegetical Commentary [2003] 17, 19ff), and most recently Elie Assis (�Haggai: Structure and Meaning.� Biblica 87 [2006] 531-541).� The following presentation of Haggai�s macrostructure leans heavily upon Assis, and is largely a summary of his work.

[5] The chiastic-inclusio arrangement of the dates in 1:1 and 1:15 has been noted by a few scholars: Pieter Verhoef, �Notes on the Dates in the Book of Haggai,� in Text and context: Old Testament and Semitic Studies for F.C. Fensham (1988), 262. C.L. Meyers & E.M. Meyers, Haggai, Zechariah 1-8 (1987) 36.� Frank Yeadon Patrick, Haggai and the Return of YHWH (Ph. D. Dissertation, Duke University, 2006), 107-108.� To my knowledge, no one has argued for the more comprehensive chiastic patterning I am proposing here.�

[6] The one exception to this is 1:15a, where the vd,xo+l; of 1:1c drops out.� However, this change is not without reason.� When the day changes from first to the twenty-first, in order to maintain the numerical lexical balance of the first concentric series in 1:1, 15 (4 words [A], 2 words [B], 3 words [C]) vd,xo+l; had to be dropped.�

[7] Note the absence of vd,xo+l; in B′′ and B′′′, ~Ay�B. in C′′ and C′′′, as well as the description of Darius as %l,M,(h; in A′′.�

[8] Note how C′′′ has only two words because of the absence of the vd,xo+l; found in C′′. Furthermore, because of the absence of %l,M,(h;, A′′ has only three words, compared with the four words of A′.

[9] Hag. 2:2-3 (NASB)

[10] We use the term �concentric arrangement� rather than �chiasm� because verses 2-3 lack the clear lexical duplications characteristic of true chiasms. Our concentric arrangement is based upon the following broad parallels. First, verses 2a and 4c both make mention of an addressee described in reference to his relationship to the land (governor/inhabitants). Second, 2b and 4b are exact duplicates in their description of the priest:� lAd�G�h; !he�Koh �qd�c�Ahy>-!B, [;vu�Ahy>. Third, 2c and 4c are parallel in that they each mention an addressee without any expansive description (note the contrast between the description of Zerubbabel in 4a and 2a!). Fourth, 3a and 3c are parallel in that each question asks the hearer to compare the former and latter temples.� In 3a, the comparison is explicit, in 3c it is implied.�

[11] Hans Walter Wolff,� Haggai: A Commentary (1988) 72.

[12] Wolff actually argues that 2:4b �can certainly be assigned to the editorial additions of the Haggai Chronicler� (73), but this is entirely unnecessary. Wolff�s comment is very strange, in view of the fact that he otherwise accepts the literary integrity of Haggai 2:1-9. The myopic eyes of critical-liberal fundamentalism apparently cannot see beyond their own paradigm�it must be imposed somewhere on the text!

[13] In addition to the fourfold revelatory declaration (�thus says the Lord�), we note further that this subunit is delimited by the strong hko� yKi (�for thus��) of 2:6 which serves to introduce a new section. Furthermore, though the revelatory declaration occupies the final position in each verse (2:7, 8, 9b, 9d), it also opens the subunit (2:6a) and thus brackets the entire section.�

[14] A similar chiasm based upon prosodic rhythmic structure has been proposed by Duane Christensen, �Impulse and Design in the Book of Haggai.� JETS 35:4 (Dec. 1992): 454.� Cf. J. Alec Motyer�s proposal in The Minor Prophets, ed. McComiskey (1998) 986.� Not surprisingly, David Dorsey has also suggested a chiasm here: The Literary Structure of the Old Testament (1999) 316.

[15] As James Kugel, J.P. Fokkelman, and Robert Alter have shown, all Hebrew parallelism is characterized by expansion and growth rather than mere repetition (contra Lowth).� They have formulated this principle in the following way: �A, what is more B.�� Let us take Is. 49:23b as an example:

������� A � With their faces to the ground they shall bow down to you

����������������������� B � They shall lick the dust of your feet

The B-colon doesn�t simply duplicate the A-colon, but rather enriches it.� The humiliation of Israel�s enemies is deeply intensified as they �bow their faces to the ground� and �lick the dust of their feet.�� For further discussion see Kugel, The Idea of Biblical Poetry (1981).� Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry� (1985) 3-26.� Fokkelman, Reading Biblical Poetry: An Introductory Guide (2001) 24-30, 61-86.� What they apply to parallelism between cola, I am applying to parallelism within chiasmus.�

[16] The promise of God in Leviticus 26:40-45 is evidence of the preeminently gracious character of the Mosaic administration.� God doesn�t simply bring Israel back from exile in spite of the principle of the Mosaic administration, but rather the promise of forgiveness and return is constitutive of it.� The return is not grounded simply on the remembrance of God�s covenant with Abraham (Lev. 26:42), but with the gracious covenant he made with the Israelites at Sinai (Lev. 26:45; cf. Hag. 2:4-5). For Haggai, the Exodus covenant does not stand in antithetical contrast to the eschatological future.� Rather, it is protologically constitutive for the fullness of the grace of the Spirit�s presence in the age to come.�

[17] Interestingly, during the time of Ezra-Nehemiah (of which the prophecy of Haggai is a part) the feast was observed in a way it had not been since the days of Joshua (Neh. 8:17).� Though Neh. 8:18 seems to indicate that the feast had not been kept at all from Joshua to Nehemiah, we know from Chronicles that Solomon observed it (1 Kings 8:2; 2 Chron. 7:8; 8:13).� In fact, Ezra 3:4 states that the returned exiles kept the Feast of Tabernacles upon their return in 538/7.� The prophecy of Haggai 2:1-9 comes in 520, and would thus reflect the reestablished practice among the returned Israelites.�

[18] We do not intend in any way to impose this dynamic upon Haggai�s prophesy.� Indeed, Haggai�s own terminology and vocabulary suggests it.� Note especially the correlation of !Av+arIh� (2:3, 9) and �!Arx]a;(h� (2:9).��

[19] The language of Hag. 2:21-22 is also indicative of a new exodus motif.� The projected overthrow of �horse and rider� and �chariot� recalls the Song of Miriam and the Song of the Sea (Ex. 15:1, 21).� The overturning of the royal thrones and power of the nations also recalls the overthrow of Pharaoh in the protological Exodus (cf. Ex. 15:4).�

[20] The typological connection between the Sinai theophany and the eschatological upheaval is explicit in Haggai�note the phrase �once more� (2:6).� This is obviously an antecedent reference to the Exodus event mentioned in 2:5, thus clearly correlating the two events.� Haggai�s theophanic eschatology is reinforced by the other prophets (Jer. 23:7-8; Is. 63:11-12; Mal. 4:1) who speak of the future in terms of the Mosaic period.� Psalm 68:8 and 77:16-17 both speak of the theopanic �shaking� of the earth at Sinai.� The New Testament (Heb. 12:18-29) ties these prophetic strands together in drawing a parallel between Sinai/Zion, explicitly referencing Hag. 2:6-7, and making reference to God as a consuming fire (Heb. 12:29; Deut. 4:24).� Cf. Geerhardus Vos, The Eschatology of the Old Testament, ed. James T. Dennison, Jr.� (2001) 105-6.�

[21] Compare Haggai�s prophecy with the famous Behistun inscription in which Darius explicitly uses this language (Column 1, Line 1): �\ adam \ D�rayavau� \ x��yathiya \ vazraka \ x��yatha \ x��yathiy� (I am Darius, the great king, king of kings).�