[K:NWTS 23/3 (Dec 2008) 54-74]

In recent years, studies of the book of Haggai have been marked by a stark shift in methodology. With the rise of literary and structural analysis in biblical interpretation, both form and redaction criticism have begun to loose their dominant grip on the study of Haggai. Whereas this earlier scholarship found Haggai 1 to be a fertile site for the discovery of various layers of contradictory editorial interpolations and modifications, more recent studies have been calling attention to its essential literary-structural unity and integrity. A keystone of this new approach has been the discovery of a chiastic pattern in Haggai 1. While some disagreement remains regarding the details of this pattern, this attempt at narrative and structural analysis is encouraging.[1]�

In this article, we propose to build upon this recent work in order to further answer some of the critical theories regarding the redaction of Haggai. Our thesis is that the prophetic proclamation of Haggai 1:1-15 is a single unit, arranged in a tightly knit and comprehensive chiastic pattern. However, the significance of this structural pattern cannot be reduced to mere aesthetics, nor does it simply serve as a constructive apologetic for the unity of the text against destructive critical views. As we shall demonstrate in the second part of this article, the chiastic structure of Haggai 1:1-15 serves to rhetorically reinforce one of the main theological themes of the post-exilic prophetic writings�the theme of eschatological reversal. We will begin our study with a brief examination of the critical analyses of Haggai 1, then present our case for a comprehensive chiastic pattern in the same chapter, and finally present a brief biblical-theological analysis of Haggai�s message in light of our structural conclusions.

Speaking in general terms, there has been widespread agreement among critical scholars that various redactional layers can be detected throughout the text of Haggai. While each proposal has differed (sometimes markedly) in both exegetical detail and theological analysis, nearly all of them have begun with the fundamental assumption that the oracular and narrative portions of the book come from different authors or editors.[2] Though there are as many theories as there are scholars with regard to the details of Haggai�s redaction, all of them nevertheless agree on this foundational axiom divorcing the oracles and narrative framework of Haggai�s prophesy. What follows is a brief survey of some of these critical proposals.[3] While by no means exhaustive, this study will allow us to appreciate the helpful role that structural and literary analysis can play in coming to a consensus on the textual integrity of Haggai�s prophesy.

The first major proposal was that of Peter Ackroyd.[4] He broke down the redaction of Haggai into four distinct periods:

- First, there was the original oral delivery of the prophesies.

- Second, there was the oral transmission of these prophecies.

- Third, there was an early written collection which added 2:3-5, 11-14a.

- Fourth, one to two centuries later, a redactor expanded and reinterpreted the prophecies, and added dates.

- Finally, some interpretive glosses were added (2:5a, 9b, 14b, 17b)

The theological agenda of the later editors was to refute the claims of the Samaritans in the Second Temple period. Ackroyd regarded the oracular portions as the �Haggain� original, while the �narrative framework� was regarded as the result of later editors.

Building upon the work of Peter Ackroyd, W. A. M. Beuken, also sought to isolate the oracular and editorial layers of the book.[5] According to Beuken, later editors (one to two centuries after Haggai) transformed these original oracles into larger �scene-sketches� (Auftrittsskizzen), which included the additions of Haggai 1:3-11, 12b, and 2:15-19. Its final form was produced by a �Chronistic� editor, who arranged the book into what he called �chronistic episodes�. This �Chronicler� added introductory formulae (1:1, 2:1-2), as well as statements about the effects of the prophet�s words (1:12-14).

The theological agenda of each editor, according to Beuken, breaks down as follows. The first editor, the �scene-sketcher,� was a Judean landowner who had not gone into exile. He favored a return to the pre-exilic conditions, and thus condemned all forms of Jewish syncretism. By contrast, the final redactors emphasized the continuity of the Davidic line to refute Samaritan claims about the temple. In addition, these redactors emphasized repentance and the power of prophecy in the history of God�s people. By thus reinterpreting and resituating Haggai�s prophecy, this Chronistic editor reframed Haggai�s message to fit the agenda of later anti-Samaritan Judeans.[6]

Later, R. Mason proposed an alternative to Beuken�s analysis.[7] He agreed with Beuken that there were several redactional layers in Haggai, but attributed them to an editor with a more Deuteronomistic orientation (415-16).� Mason sees the following texts as the editorial framework of Haggai: 1:1, 3, 12, 13a, 14, 2:1, 2, 10, and 20 (414). Though different in these details, Mason�s approach as a whole differs little from Beuken. Both agree in dividing the book into narrative and oracular sections, and attributing each of these to separate writers/editors with distinct theological agendas. As Mason himself states, �No one can treat any aspect of the books of Haggai and Zechariah i-viii without being deeply indebted to Beuken�s work, even where he may find himself questioning some of the conclusions� (414).

More recently there is the proposal of Hans Walter Wolff.[8] Following Beuken and Mason, Wolff argued that the final version of Haggai has come down to us is in the form of a �chronicle,� though it originally consisted of several isolated prophetic utterances. Wolff believes that the various layers, consisting of the prophetic oracles themselves, the scene-sketcher, and the Haggai Chronicler, are clearly discernible (34). He summarizes these layers in terms of three �growth rings�:

- First, there is the prophetic proclamation itself (1:4-11; 2:15-19; 2:3-9; 2:14; 2:21b-23).

- Second, there are the scene-sketches (Auftrittsskizzen), composed by the Haggai Chronicler. These consist in the introductory formulas (1:1-3, 1:15a; 1:15b-2:2; 2:20-21a), and various supplementations of the scene-sketches (2:4, 15, 17b, etc).

- Third, there are various later interpolations (the last words of 2:18, first four words of 2:19ab, and the LXX expansions of 2:9, 14, 21, 22ba).

For Wolff, these distinctive features can be summarized as follows. First, the Haggai Chronicler addresses the governor, high priest, and people, while the �scene-sketcher� addresses only �this people� (1:12, 13). Second, the �scene-sketcher� calls Haggai �Yahweh�s Messenger,� while the Haggai Chronicler calls him �the prophet� (1:1, 3; 2:1, 10). Third, whereas the Haggai Chronicler introduces the revelation of God�s word as �the word of Yahweh came by�� (1:1, 2; 2:1, 10, 20), the scene sketcher uses �thus has Yahweh said� (8 times) or �saying of Yahweh (Sabaoth)� (12 times).

Many other scholars have proposed other similar analyses of the redaction of Haggai, including Janet Tollington and R. J. Coggins.[9] But it is not necessary to outline them all in detail here. The important thing to note is that nearly all of these earlier studies on the structure of Haggai share the common assumption regarding the clear contrast between oracular and narrative material. By setting these aspects of the text in sharp antithesis, scholars would then deconstruct the present text and the theological agendas of its various editors. The basic principle underlying this approach was clearly articulated by Herman Gunkel (albeit in a different context), one of the fathers of form criticism.

It is the common fate of older narratives which are preserved in later form that certain traces which made sense in the earlier contexts are transmitted in the newer account, in which they have, however, lost their context. Such old traces, fragments of an earlier whole, without context in the present account, and hardly understandable from the standpoint of the one who finally reports it, disclose to the investigator the existence and the particular traces of an earlier form of the existing narrative.[10]

Beginning with the assumption that the book in its present form is fraught with literary and stylistic contradictions, they then proceed to fragment the book into its original form(s), and trace the editorial development of the prophecy.

However, in recent years, studies in Haggai have been marked by an encouraging methodological shift. Rather than tracing the redactional history of the narrative and oracular portions of Haggai�s prophesy, these newer studies have sought to emphasize the coherent literary unity of the text in its final form. Utilizing new methods of narrative, structural, and poetic analysis, these scholars have begun to appreciate anew the literary beauty and artistry of Haggai�s prophesy. Some still presuppose an editorial process in the formation of Haggai�s prophesy, but most are much less confident about discerning the details of that process.

For example, though Myers and Myers have argued that an �editorial framework has been superimposed upon a core of original material,� they nevertheless insist that �there is little hope or even purpose in separating out all of the individual units.�[11] Rather, there is a clearly discernable literary continuity between the oracular and narrative portions of the text. Likewise David Peterson, though he too still presupposes a redactional history to the book, openly refers to the various critical reconstructions as �unconvincing� and even �artificial.�[12] John Kessler, in his recent monograph on Haggai has also emphasized this point. Though he seems eager to assure his colleagues that he is not challenging the validity of form and redaction-critical methods, he admits that Haggai�s �oracles and frameworks share a good deal of common ground,� and that �the book ought to be read as �an integral whole.��[13] Michael Floyd has been so impressed with the unity of the book that he has urged his peers �to reconsider the whole notion of the narration in Haggai as an editorial device framing composites of originally separate prophetic speeches.�[14] Some scholars have moved even farther away from form and redaction criticism, focusing almost all their attention on the literary shape of the text itself. Elie Assis has contributed several articles in this vein on the structure of Haggai, delineating both its macrostructural and microstructural literary coherence.[15] Frank Yeadon Patrick has also argued strenuously that �the book is best read as a cohesive and artistic literary composition with clearly identifiable communicative goals.�[16]

However, though most recent scholars have recognized to some degree the literary unity of the final form of Haggai�s prophecy, most of them have not fully given up their redaction-critical presuppositions. Many of them have yet to come to grips with the far-reaching methodological consequences of such a conclusion about the literary unity of the book of Haggai. The difficulty (as we see it) is that critical scholars began their analysis of Haggai with the assumption that various portions (oracular vs. narrative material) of Haggai were in obvious tension with one another. Varying stylistic, terminological, and theological differences between these two portions were assumed to be obvious evidence of different editorial hands at work in the development of the prophecy. However, recent research has shown the final form of Haggai demonstrates a carefully crafted, and even artistic literary unity. Some of the apparent stylistic discrepancies are now recognized as integral components of carefully crafted literary artistry.� The evidentiary support for the redaction-critical approaches has thus apparently been removed from beneath the critics� feet. Yet these approaches to exegetical analysis of Haggai continue to be perpetuated, even with the plain admission that the evidence supporting such an approach is wholly lacking. It is becoming clearer that such approaches have been based far more in epistemological, hermeneutical, and philosophical precommitments than in the concrete character and scope of the prophetic text.� Rather than dealing with the actual text as it stands, these critical methods have simply imposed an alien paradigm on to the biblical text, thus destroying the beautiful literary unity and artistry of biblical revelation the way a vandal defaces a priceless piece of artwork.�

Nevertheless, with these more recent approaches to Haggai, many scholars have begun to analyze the structure of Haggai�s prophesy anew, including his opening chapter. Generally speaking, a new consensus is developing that views Haggai 1:1-15 (formerly a favorite target of redaction-critical analysis) in its present form as a coherent literary whole. Specifically, many scholars have noted the chiastic arrangement(s) of Haggai 1:1-15. However, scholars are not entirely agreed as to the precise details of this chiastic arrangement. David Dorsey (who has had no trouble finding chiasms throughout the Bible) has argued for a chiastic structure in 1:2-11, though in our opinion his points of correspondence are purely thematic.[17] Likewise J. Alec Moyter notes a possible chiastic arrangement to 1:1-11, but, like Dorsey, his suggestion is purely thematic and has little basis in the lexical, grammatical, or syntactical shape of the text.[18] Furthermore, his analysis breaks off 1:12-15 from the rest of the chapter, thus falling short of demonstrating the unity of the whole chapter.� Duane Christenson also sees a chiastic pattern in Haggai 1, but bases it on �rhythmic patterns� rather than concrete textual correspondence.[19] Kessler has noted various points of correspondence at the beginning and ending of Haggai 1 and although he misses the chiastic inclusion of the dates, he has proposed a chiastic arrangement of 1:4-11 that is similar to ours.[20] Elie Assis[21] has analyzed Haggai�s careful patterning in 1:1-11, noting the chiastic arrangement of 1:6 and 1:9, as well as several correspondences in 1:4-6 and 1:7-9. However, these treatments fail to note the chiastic arrangement of the dates in 1:1 and 1:15, and both fail to integrate the whole of chapter 1 as a unified structural whole. While all these studies have put us on the right track, all of them fail to provide a comprehensive structural analysis of Haggai 1.

However, Frank Yeadon Patrick�s recent work is a notable exception. He has argued for a chiastic arrangement in Haggai 1 similar to the one proposed here.[22]�

A�Beginning Date (1:1a)

��������������� B�Introduction of Characters and Problem (1:1b-2)

������������������������������� C�Curses Reconsidered (1:3-7)

����������������������������������������������� D�Actions of the people and the Deity (1:8)

������������������������������� C�Curse Conditions Explained (1:9-11)

������������ � B�The Characters Respond / Rebuild the Temple (1:12-14)

A�Concluding Date (1:15)

Together with Myers and Myers,[23] Patrick is the only scholar I have come across who has also noticed the chiastic arrangement to Haggai�s dates in 1:1 and 1:15. In addition, his proposal is superior to the others in that it does not break off 1:1-3 or 1:12-15 from the rest of the chapter, but integrates it into the rest of the chapter as a literary whole. Furthermore, in our estimation, Patrick has insightfully grasped the theological significance of the reverse chiastic pattern in Haggai 1. The chiastic structural reversal is a signal for a greater prophetic reversal from exile to return.

All of these scholars have helped us move forward in understanding Haggai 1. However, no one has offered a detailed analysis of the structural patterns of the entirety of Haggai 1 that definitively challenges the previous critical consensus. It is precisely this that we propose to do in this article. In so doing, we hope to provide a helpful antidote to the more destructive analyses of the text of Haggai 1, and hopefully protect Haggai�s inspired masterpiece from further desecration at the hands of critical vandalism.

In a previous article, we have noted the importance of dates in the prophesy

of Haggai.[24] In fact, the entire book is arranged in four sections, each demar- cated by the appearance of a date and a revelatory preface (1:1, 2:1, 2:10, 2:20). However, the integrity of Haggai 1 as a single unit is debated by critics and conservatives alike.� While some argue that the entire chapter is a holistic unit, Peterson,[25] Floyd,[26] Verhoef,[27] and others divide it into two sections (1:1-11, 1:12-15). At first glance, this does not appear to be without warrant, for a date does occur in 1:15, which may suggest that 1:12-15 is a separate unit.

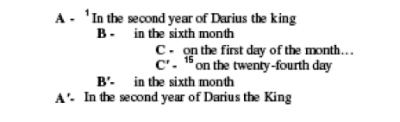

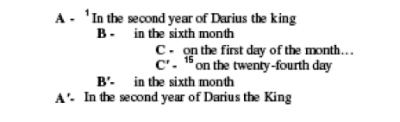

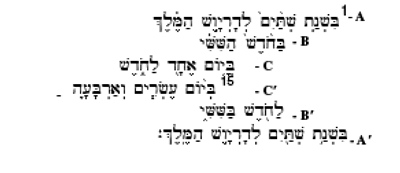

However, a closer examination of these dates supports the literary unity of the entire first chapter. First, we note that the dates in 1:1 and 1:15 are given in full (day, month, year), which does not always occur in Haggai. Also, the name �Darius the king� appears in each. This suggests that the dates in 1:1 and 1:15 are a broad inclusio bracketing the entire chapter. Secondly, these dates do not merely repeat, but they do so in a chiastic pattern. While 1:1 follows the pattern of year-month-day, 1:15 reverses the order to day-month-year.

There are some differences between the two dates. Not only does the day itself change (first day/twenty-fourth day), but the preposition prefixed to ��vd,xo�� does as well (l/B). Furthermore, in 1:1 the day is described in terms of its relationship to the month (�the first day of the month�), whereas in 1:15 it is simply described as a numerical day (�the twenty-fourth day�). However, these differences pose no problem for our chiastic arrangement. Not only do the time-markers �year-month-day� in 1:1 clearly reverse themselves to �day-month-year� in 1:15, the phrase �%l,M,�h; vw<y��r>d�l.� is precisely duplicated as well. Furthermore, the difference between 1:1c and 1:15a noted above can be easily explained. The number 24 in Hebrew (as in English) requires two words (h[��B�r>a;w> ~yrI�f.[,), whereas the number 1 only requires one (dx��a,). To add the word �month� to 1:15c would bring prosodic imbalance to Haggai�s carefully arranged inclusio. Note the prosodic balance on the lexical level. In the AA′ sections, there are four words. In the BB′; there are two words. In the CC′, there are three words. Such analysis reveals to us the careful and intricate nature of the hand of the prophet as he etches his prophesy. Only someone paying close attention to prosodic symmetry and structural balance would pen this the way our author did.

The chiastic nature of Haggai�s temporal inclusio suggests a possibility for the rest of this section: is there a chiastic arrangement evident in the entire chapter? Let us work our way through the chapter to see what the prophet has for us.

First, we note the repetition of characters at the beginning and end of chapter one. In 1:1-2, four characters appear: Haggai the prophet (aybi�N�h; yG:�h�), Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and Joshua the son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and �these people� (�hZ<h; ~[��h�). In 1:13-14, these same four characters reappear: Haggai, the LORD�s messenger (hw��hy> %a:�l.m; yG:�h�), Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, Joshua the son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and all the remnant of the people (~[�_h� tyrI�aev lKo�). While the descriptions of Zerubbabel and Joshua remain the same in each, those of Haggai and the people slightly differ.

Second, each appearance of these four characters is followed by a statement describing the work of the people. In 1:2, the LORD states that the people are saying �the time has not yet come to rebuild the house of the LORD� (tAn*B�hil. hw��hy> tyBe�-t[, aBo�-t[, al{�). However, when we come to 1:14, we read that �they came and worked on the house of the LORD of hosts, their God� (~h,(yhel{a tAa�b�c. hw��hy>-tybeB. hk��al�m. Wf�[]Y:w: �Wabo�Y�w:). In addition to the thematic repetition of �work� and �building� these verses are linked by the duplication of the phrase �house of the LORD� (hw��hy tyB,) and the root �awb.�

As we press downwards towards the center of Haggai�s first chapter, we see another point of correspondence and duplication in 1:4 and 1:9c. In 1:4, the prophet sets in contrast the people�s well-built paneled houses (~ynI+Wps. ~k,�yTeb�B.), with the house of the LORD which lies in ruin (bre(x� hZ<�h; tyIB:�h;w.). In 1:9c, this contrast returns: �my house which lies in ruins� (bre�x� aWh�-rv,a] �ytiyBe) stands in contrast to �his own [the people�s] house� (At*ybel.). In keeping with the chiastic nature of this chapter, this repetition of the people�s house vs. God�s house also takes a chiastic form[28]:

��������������� 1:4b�~ynI+Wps. ~k,�yTeb�B

������������������������������� 1:4c�bre(x� hZ<�h; tyIB:�h;w.

������������������������������� 1:9c�bre�x� aWh�-rv,a] �ytiyBe

��������������� 1:9d�At*ybel.

In the center of the chiasm, the word �brx� is repeated. Furthermore, though the form of the word �house� (tyIB\) changes from 1:4c to 1:9c, the referent in each is to the house of hw��hy>. At the outsides of the chiasm, the word �house� is repeated, each time with reference to the people�s own houses. As we press further towards the center of Haggai�s chiasm, we are pressed down towards his central concern: the hw��hy> tyB/.

The prophet further amazes us with another explicit parallel duplication. In 1:5a and 1:7 the revelatory formula �thus says the LORD of Hosts� (tAa+b�c. hw��hy> rm:�a� hKo�) is precisely repeated. This formula marks the two central sections of Haggai�s chiastic arrangement. Within the subunits demarcated by this revelatory formula, we note the following points of correspondence:

However, there is a difference between the two sections. In the first section, the description of the futility of Israel�s existence (expecting much, receiving little) is fivefold: sow/bringing in, eat/no satisfaction, drink/no fill, clothes/no warmth, wages/bag with holes (1:6). In the second section, the command for Israel to build the Lord�s house is fivefold. Note the five verbs: �dbeK�a,w>�AB��Wn�b.W�~t,�abeh]w:�Wl�[].�� The fivefold description of Israel�s futile disobedience in building their own houses is reversed in a fivefold instruction to Israel to build the Lord�s house!

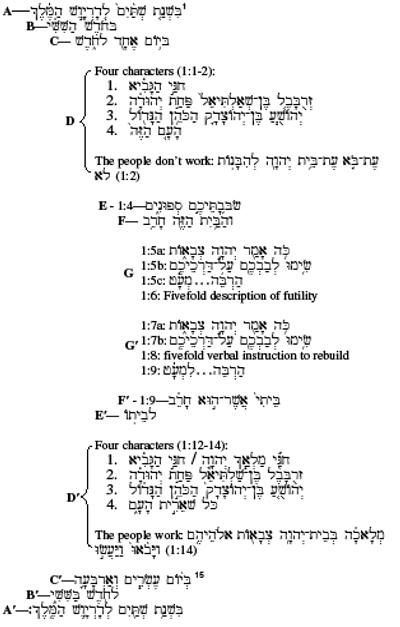

Let us now chart our findings in one comprehensive picture, first in English, then in Hebrew:

It goes without saying that this chiastic arrangement, if valid, has monumental significance for the current scholarly debate about the structure of Haggai. First, it most certainly establishes the entirety of 1:1-15 as a distinct unit, contra Verhoef and others who divide it up into two sections.[30] Second (and more importantly), this chiastic arrangement also poses deadly problems for the various form and redaction-critical analyses of Haggai. For example, Wolff assigns 1:4 to the original prophetic proclamation, whereas 1:14 comes from the hand of the Haggai Chronicler. However, as we have seen, each of these plays an integral part in the chiastic reversal: the transition from no work (1:4) to work (1:14). It seems highly unlikely to this writer that the central dramatic reversal in Haggai 1 would be the chance result of two different tendentious editors!�

But the problems such a chiastic structure poses for form and redaction-critical approaches lies not so much in the fact that it challenges the details of various proposals to the redaction of Haggai, but in the more fundamental hermeneutical questions it raises. If the present text of Haggai 1 demonstrates a cohesive and comprehensive literary unity, on what basis can we proceed to deconstruct the text into its (allegedly) original constitutive parts? If those elements which once appeared to be in irresolvable tension with one another now appear as essential elements of a integrated literary pattern, how do we justify disintegrating this cohesive rhetorical unity? The conclusion seems inescapable to us, in light of the clear literary unity of Haggai 1, that such approaches (in spite of their long-standing dominance in the study of the prophetic literature) can only serve to obstruct a true understanding of the text of Haggai�s prophecy. Rather than seeking to understand Haggai�s prophecy as a single text (let alone as the revealed Word of God), these approaches stand over the text and force it into a hermeneutical model foreign not only to its inspired character, but also its Ancient Near Eastern literary milieu.

This conclusion will become even more apparent when one begins to analyze the theological significance of this chiastic paradigm for the message of Haggai 1. In other words, Haggai�s chiastic structure is more than mere aesthetics; indeed, it is even more than a powerful apologetic antidote to the various destructive critical views proposed in the past century. Rather, the chiastic pattern of Haggai 1:1-15 is rhetorically reflective of the prophet�s redemptive-historical message to post-exilic Israel. Indeed, Haggai�s chiastic pattern is marvelous example of the rhetoric of the post-exilic prophetic reversal.

Haggai and Zechariah represent the dawn of a new era for the prophets of Israel. Prior to the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC, Israel had been the recipient of the prophetic ministry of the �former prophets� (Zech. 1:4). Israel�s failure to heed their message resulted not only in the beginning of the exile, but also a period of silence in the progressively unfolding revelation of the Lord of Hosts. The destruction of Jerusalem marked the end of one era (the Monarchy) and the beginning of a new (the Exile).� A reversal of anti-eschatological proportions had taken place. Israel was removed from the land of blessedness (Canaan), and cast out to the land of cursedness (Babylon). Yet God did not leave his people without hope. He promised that he would one day visit Israel with many happy returns.

The end of Judah�s exilic nightmare came with the decree of Cyrus and the returns of Ezra and Nehemiah to Judah. In the midst of this transition, Haggai and Zechariah helped to enunciate the dawn of a new age of hope for the people of God. These �latter prophets� proclaimed to God�s people the return of God�s glory in the �latter days��a dramatic historical reversal of eschatological proportions. They proclaimed a reversal of the temple: from destruction to construction. They proclaimed a reversal of Israel�s covenant disobedience: from faithlessness to faithfulness. They proclaimed a reversal of Israel�s covenant-communion with God: �return to me, that I may return to you� (Zech. 1:3).

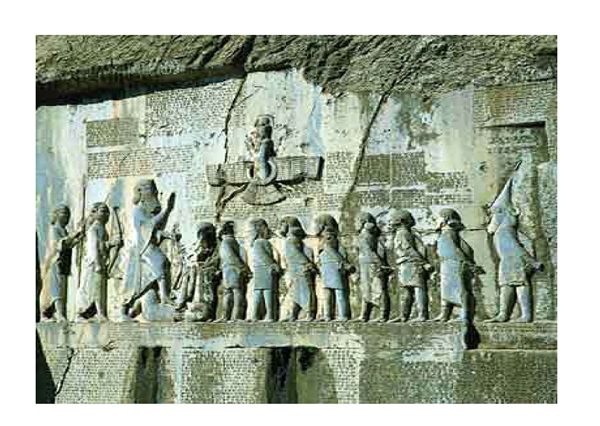

But the return was not all that was expected. Immediately, the new Israel began to face bitter hardship from the surrounding peoples. Indeed, these returned exiles in Haggai�s day were surrounded. They were surrounded by the oppressive rule of the Medo-Persian Empire. Darius I, son of Hystaspes, had gained control of the Persian Empire after a brief period of internal strife after the death of Cyrus�s son Cambyses. Whatever hopes the conquered nations had of the dissolution of the 6th century B.C. Iranian regime were dashed with the accession of Darius. After his accession to the throne, Darius consolidated his power, and divided his kingdom into several satraps. This consolidation is celebrated in the famous �Behistun Inscription� in the mountains of Western Iran.

The picture is well worth the several thousands words which tell its story. The winged figure at the top of the monument is likely the Persian God �Ahura-Mazda.� Ahura-Mazda was worshipped as the Creator-God of the Persians (whether in a henotheistic or monotheistic sense is debated). In contrast to Ahura-Mazda and his creation, stood Anga Mainyu and �uncreation.� This dualistic orientation precipitated a conflict between what they referred to as the Arta and the Druj (the truth and the lie). All things lie on one side of this dualistic construct: light, water, fertile land, health, etc., stood on the good side; darkness, winter, drought, sickness, death, etc. stood on the other. Interpreted in light of 6th century Persian nationalism, the Arta was embodied in the comprehensive rule of the Acheamenid monarchs, whereas the Druj was represented in the various would-be usurpers of the Persian world order. The creation and order of the Persian rule (Druj), stood over against the chaos and disorder of these rogue rebellious kings.

As one can easily see from the above picture from the Behistun monument, Persia wanted to send a clear message to these potential rebels. Beneath Ahura-Mazda, standing tallest above the rest, is none other than Darius himself, the enforcer of the Arta. To his left stand his assistants. To the right stand nine conquered kings (with one on the ground under his feet). Darius is clearly presenting himself as an enforcer of righteousness and order, the �king of kings� who is above all.

Yet how subtly does Haggai proclaim the reversal of this pagan empire! Though the present time is the time of Darius the king, and Israel finds herself surrounded and bracketed on all sides by his tyrannical rule, Haggai is signaling a day when Darius� kingdom will be brought to an end. The chiastic reversal of Darius� regnal calendar in 1:1 and 1:15 is proleptic of the conclusion of this prophecy. For in Haggai 2, we no longer see Darius bracketing Israel�s eschatological future, but rather Zerrubbabel, the Son of Shealtiel. The double mention of Zerubbabel at the beginning and ending of the final prophetic unit stands in stark contrast to the dominating presence of Darius in chapter 1.

But the prophetic reversal does not only affect the pagan nations, it touches the heart of Israel herself. Indeed, Israel herself stands in need of a reversal�the reversal of her covenant disobedience into covenant obedience. Depressed, discouraged, and dejected, she is no longer giving her hands to the work God had commissioned her to do. It had been more than fifteen years since Cyrus the great made his famous proclamation to return to the land and rebuild the house of God, yet the people are saying �the time has not yet come, the time to rebuild the house of the Lord� (Hag. 1:4). She is to be filled with zeal as she goes about the Lord�s work, but the prophet finds in her only weak excuses that testify against the depth of her disobedience.

But how different Israel looks after the word of the Lord is proclaimed in her midst. Though in Haggai 1:2 the people are excusing their disobedient laziness, in Haggai 1:14 that disobedience is graciously reversed: �they came and worked on the House of the Lord their God.� Through the power of the prophetic message, Haggai stirs up the people, priest, and governor to fulfill the covenantal commission they had received from the Lord to rebuild the temple of God.

How different Israel looks now! No longer is she only concerned about her own private houses, decorating them with temple-like paneling as she seeks to bask in the material comfort of the Fertile Cresent. Now her heart is fixed on the true center of her life as the people of Israel: the house of God! How marvelously Haggai reinforces this wonderful change of heart-orientation by means of chiastic arrangement. The double mention of �your own house� and �the house of the Lord� of 1:4 is exactly reversed in 1:9.

������ A - 1:4�Your paneled houses�

������������������������������� B - �this house lies in ruins

������������������������������� B′ - 1:9c��my house which lies in ruins

������ A′ - �each to his own house

What was formerly central (their own houses) now lies on the periphery. The new orientation of her life and heart has been reversed to what is truly her highest end: the house of God. The prophet has rhetorically reinforced Israel�s theocentric transformation by means of an intricate chiastic arrangement.

And this transformation has taken place by one central instrumentality: �the word of the Lord of Hosts.� In 1:7 and 1:9, we have a duplicate repetition of the divine disclosure formula: �Thus says the Lord of Hosts.� It is God, by his word, who sovereignly, graciously, and persuasively moves Israel back to the center of her life. The dual declaration that Haggai�s message is indeed the word of the Lord of Hosts brackets this central orientation at the heart of his prophecy. As Israel is inundated by the temporal curse-sanctions of the Mosaic era for her unfaithful disobedience (1:6, 9-11), she is being prodded to consider what ought to be the true center of her life: the temple and house of the Lord. The center of Haggai�s message, both structurally and theologically, is the command we read in Haggai 1:8: �Go up into the mountains and bring down timber and build the house, so that I may take pleasure in it and be glorified, says the Lord.��

The glory of God in the house of God�that is Israel�s past glory, partial present possession, and future eschatological hope. As Israel�s life centers anew on the glory of that house, nothing less than a complete reversal takes place. Pagan rule is reversed in the shalom-like Messianic kingdom of peace; covenantal disobedience is sovereignly and graciously reversed into faithful covenant obedience; Israel�s shameful self-centered focus on her own houses is marvelously reversed into a glorious God-centered focus on his house. How marvelously Haggai has reinforced his message about the post-exilic prophetic reversal!

It is this eschatological and redemptive-historical reversal that is mirrored here in Haggai 1:1-15. The prophet�s artistic and literary skills are impressive. He has even conformed his rhetorical method to the flow of redemptive history! The prophet carefully arranged his words in a reverse chiastic fashion. He meticulously arranges his prophetic word in a reverse rhetorical pattern in order to persuade Israel�in order to draw his hearers�into the life and glory of Israel�s reversal.

And Haggai�s message of eschatological reversal comes not only to Israel, but also to us. These things happened to Israel for an example, but they were written down for our instruction, upon whom the ends of the ages have come (cf. 1 Cor. 10:11). The written record of Haggai�s oracular proclamation signals to us that its message will continue to have abiding significance into the future. Indeed, Haggai desires that we too participate in the glory of the construction of the latter temple. His spiral-like reversal of Israel�s life in the former is recorded for you, that you might be caught up in the whirl-wind effects of his prophetic proclamation. The people of God who live now during the last days are part of the eschatological temple, of which Christ Jesus is the chief cornerstone. As they sojourn as strangers and exiles, with the effects of sin and curse still all around them, they (with Israel) have the word of the Lord to stir them up unto his zealous service. For Jesus, their great prophet, priest, and king, abides with them to comfort, encourage, and strengthen them, even unto the end of the age.

[1] As we shall see, not all scholars are agreed as to the extent of this chiastic pattern. Most attempts have lopped off 1:1 and 1:12-15 as a later appendage to the chiastically arranged oracles of 1:2-11.

[2] Critics use the term �oracular portions� (or the equivalent) in reference to that aspect of Haggai�s prophecy that records the actual vocal/audible disclosure of the prophet. In contrast to this, the �narrative portions� of Haggai refer to the prefatory statements introducing the prophecies, their concluding statements, as well as several editorial comments interspersed throughout. Thus, for example, Hag. 1:1-2a would be part of the �narrative framework� of Haggai 1, while Hag. 1:2b would be an �oracular portion� of the book.

[3] In addition to my own study of the primary documents (where available in English), I have made use of the following surveys of the interpretation of Haggai: John Kessler, The Book of Haggai: Prophecy and Society in Early Persian Yehud (2002) 18-22, 31-57. Frank Yeadon Patrick, Haggai and the Return of YHWH (Ph. D. Dissertation, Duke University, 2006) 4-56.

[4] The basics of Ackroyd�s view are outlined in the following two articles: Peter Ackroyd, �Studies in the Book of Haggai� Journal of Jewish Studies 2 (1951): 163-76; �Studies in the Book of Haggai� (Continued from Vol. II � No. 4)� Journal of Jewish Studies 3 (1952): 151-56.

[5] W. A. M Beuken, Haggai-Sacharja 1-8 (1967).

[6] Cf. the comments of Kessler (19)

[7] Rex A. Mason, �The Purpose of the �Editorial Framework� of the book of Haggai,� Vetus Testamentum (1977): 413-21.

[8] Hans Walter Wolff, Haggai: A Commentary (1988).

[9] Janet Tollington, Tradition and Innovation in Haggai and Zechariah 1-8 (1993). Idem, �Readings in Haggai: From the Prophet to the Completed Book, as Changing Message in Changing Times,� in The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times (1999). R. J. Coggins, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi. Old Testament Guides (1987).

[10] Herman Gunkel, Creation and Chaos in the Primeval Era and the Eschaton: A Religio-Historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12 (2006) 6.

[11] Carol L. Myers and Eric M. Myers, Haggai, Zechariah 1-8: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (1987) lxx.

[12] David Peterson, Haggai-Zechariah (1984) 39.

[13] Kessler, 55-56.

[14] Michael Floyd, �The Nature of the Narrative and the Evidence of Redaction in the Book of Haggai.�� Vetus Testamentum 45 (1995) 473.

[15] Elie Assis, �Haggai: Structure and Meaning,� Biblica 87 (2006) 531-541.

[16] Patrick, 27.

[17] David Dorsey, The Literary Structure of the Old Testament: A Commentary on Genesis-Malachi (1999) 316.

[18] See his treatment of Haggai 1 in: The Minor Prophets: Volume Three, ed. by Thomas Edward McKomiskey (2003) 973.

[19] Duane L. Christenson, �Impulse and Design in the Book of Haggai,� JETS 35 (1992) 445-56.

[20] Kessler, 248, 111-12.

[21] Elie Assis, �Composition, Rhetoric and Theology in Haggai 1:1�11,� Journal of Hebrew Scriptures (online only) 7.11 (2007) 7, 8.

[22] Patrick, 106

[23] Myers and Myers, 36

[24] Benjamin W. Swinburnson, �The Glory of the Latter Temple: A Structural and Biblical-Theological Analysis of Haggai 2:1-9.�� Kerux: The Journal of Northwest Theological Seminary 23/1 (2008) 28-46.

[25] Peterson, 35, 41-42���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

[26] Michael Floyd, Forms of Old Testament Literature: Minor Prophets: Part Two (2000) 255.

[27] Verhoef, Peter. The Books of Haggai and Malachi (1989) 20-25

[28] This chiasm is also noted by Assis (8).

[29] Note also the repetition of �awb� in each verse in connection with the �much-little� formula.

[30] In fairness to Verhoef, he does accurately highlight the structural focal point of verse 8 (Verhoef, 21).

[31] The following biblical-theological analysis is not meant to be exhaustive. Rather, we simply aim to present the biblical-theological bones upon which a more full-orbed analysis can be fleshed out with greater exegetical detail. Our main point is to highlight the role that the eschatological prophetic reversal plays in Haggai�s proclamation in chapter 1.