[K:NWTS 24/2 (Sep 2009) 13-39]

In what follows, I wish to examine Paul’s doctrine of semi-eschatological justification. To put it another way, we will consider justification as it has already come to the church in Christ’s death and resurrection. The church’s possession of semi-eschatological justification (as her possession of all God’s semi-eschatological benefits) arises from her union with Christ, as he now possesses all the eschatological benefits of his completed work. Further, as a semi-eschatological act, it is an intrusion of God’s final eschatological declaration to the cosmos that his people are justified in him. Therefore, semi-eschatological justification possesses the finality of all God’s eschatological acts in Christ.

As we consider Paul’s doctrine of semi-eschatological justification, we will suggest that it brings something new to the people of God in this semi-eschatological period (i.e., the period between Christ’s resurrection and the final resurrection of the dead). This is not to deny the unity of justification, given equally to both Old and New Testament saints. For this unity of justification is taught by Paul in Romans 4 with reference to David. Both David and Paul were equally justified by grace alone through faith alone with respect to the essential nature of the covenant of grace, of which both the old and new covenants are administrations.

At the same time, this article will argue that Paul’s application of the term justification involves something new when applied to new covenant Christians. This newness is not found in the essential nature of the new covenant (which is identical to the old), but in its formal aspect,[2] its unique administration. This formal newness is connected to the heightened semi-eschatological nature of the present time; hence the designation semi-eschatological justification.

We will then use our insight into the nature of this newness (which itself involves forensic imputation) to argue that the essential nature of justification[3] (which it mirrors) must also have the character of forensic imputation. It will be our contention that Paul’s semi-eschatological teaching of justification enriches and supports the Reformation’s doctrine of justification. In this way, we will argue against N.T. Wright, who denies that justification essentially involves the forensic imputation of the righteousness of Christ to believers. We will begin by looking at N.T. Wright’s position so that the state of the question (and contrast) between him and the Reformation on justification is made clear.

The primary difference between Wright and the Reformation is that Wright does not believe that justification involves the imputation of Christ’s active obedience to Christians. Involved in this, Wright does not believe that justification is part of the ordo salutis. That is, he does not believe that justification is an aspect of what happens when we are savingly united to Jesus Christ. He simply relates it to the historia salutis.

According to Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and the other Reformers, Christ actively obeyed the law on our behalf. His obedience was perfect, and that obedience is declared to be ours through faith in Christ. Thus Christ did more than simply take our punishment as a passive victim. He actively obeyed the law, and his active obedience to the law involved him in actively laying down his life unto death. In this active obedience, Christ earned eternal life for us. This active obedience is then imputed to us. That is, God declares Christ’s perfect righteousness to be ours legally and judicially (we might say externally) at the same time as our internal righteousness wrought by the Spirit is imperfect (and deserving of judgment, if that is all we had).

However, Dr. Wright does not believe that God imputes the active righteousness of Christ to us, only his passive obedience. At best, he sees salvation (where we are included in it) as taking place in baptism. Therefore, justification is at best God’s declaration that we are either in the covenant or not in the covenant. That is, God is simply looking at our state as it already exists in baptism and then declaring whether we are in or not, whether we are baptized or not, whether we are in the covenant community or not. But justification does not describe how one gets into the covenant. It is not describing how one is savingly united to Christ in the covenant. Thus, it does not describe the imputation of Christ’s righteousness whereby one is constituted legally righteous and accepted by God into the covenant.

Thus, we may say Wright pulls the doctrine of justification apart, separating it into two pieces and believes only in the second piece. What we might call the first piece is God’s active imputation of Christ’s righteousness to believers (the gift of God). The second part is God’s declaring them to be righteous based upon the gift of righteousness. Since God imputes to us the righteousness of Christ and we have the perfect righteousness of Christ, then it would be clear that God could justly make a declaration that we are indeed righteous—but based upon the imputation of that righteousness, not based upon our internal righteousness. Wright only believes in the second half. That is, he only believes that justification is declaring the state that we have. He does not believe that it is imputing to us a particular state. He does not believe it is a gift of God.

From the point of view of the Reformers, God could not justly declare people righteous unless they had been imputed with Christ’s active obedience. Like Wright, Roman Catholics also believed in this second aspect of justification—at least in the future—that God will declare to the world that some people are righteous. But what will be the basis upon which they are declared righteous in the Roman Catholic view? It will be on the basis of their own obedience as wrought by the Holy Spirit. Wright disagrees with Rome when she indicates that this infusion of grace is actually justification. Wright does not believe that the infusion of grace is justification. He believes that infusion is simply baptism. Only the second aspect of this declaration (that one is already baptized) is justification.

However, neither Wright nor Rome believes that there is a first part of justification that involves the imputation of Christ’s righteousness. They do not believe that justification is the gift of God imputed to us. Admittedly, Wright, unlike Rome, believes that the second aspect of this declaration has already happened in some sense. It has already occurred based on our baptism.[4] However, he does not believe that this justification (already declared to be ours) is grounded in the first aspect of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness. Justification is not the gift of God imputed to us, even insofar as it has already occurred. However, this is precisely what distinguished the Reformation from Rome at the most crucial point.

Wright’s antipathy to the Reformation’s doctrine of justification can be seen in his own words. “In all the church’s discussions of what has come to be called ‘justification’…Paul himself is of course constantly invoked[5]…it is therefore vital, and I believe, urgent, that we ask whether such texts have in fact been misused. The answer to that question, I suggest, is an emphatic Yes.”[6]

He is emphatically against the Reformation’s use of Paul’s texts on justification. He goes on to describe how one becomes a Christian. “But if we come to Paul with these questions in mind—the questions about how human beings come into a living and saving relationship with the living and saving God—it is not justification that springs to his lips or pen. When he describes how persons, finding themselves confronted with the act of God in Christ, come to appropriate that act for themselves, he has a clear train of thought, repeated at various points. The message about Jesus and his cross and resurrection—‘the gospel’, in terms of our previous chapters—is announced to them; through this means, God works by his Spirit upon their hearts; as a result, they come to believe the message; they join the Christian community through baptism, and begin to share in its common life and its common way of life. That is how people come into relationship with the living God.”[7]

Notice he says that it is simply by a change of their hearts. That is what the Reformed churches called regeneration. The Reformation argued that regeneration alone was not sufficient because the work of the Spirit in our hearts was still imperfect. We still sin. And if God were to look simply at our hearts (to the degree that they are regenerated), he would still see sin, and as a righteous judge he would still have to condemn us. So we also needed the external robe of Christ’s perfect righteousness imputed to us—declared to be ours. That is justification; it is the imputation of righteousness. Wright denies this. For him, this is not what justification is about.

Wright continues: “If you say that this is what you mean by justification by faith, I reply that we must take note of the fact that when Paul is setting out this train of thought, as he does (for instance) in 1 Thessalonians 1, he does not mention justification. That is not what he is talking about. If you respond that the entire epistle to the Romans is a description of how persons become Christians, and that justification is central there, I will answer, anticipating my later argument, that this way of reading Romans has systematically done violence to that text for hundreds of years, and that it is time for the text itself to be heard again. Paul does indeed discuss the subject matter, which the church has referred to as ‘justification’, but he does not use ‘justification’ language for it. This alerts us to the negative truth of McGrath’s point. Paul may or may not agree with Augustine, Luther or anyone else about how people come to a personal knowledge of God in Christ; but he does not use the language of ‘justification’ to denote this event or process. Instead, he speaks of the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus, the work of the spirit, and the entry into the common life of the people of God.”[8]

Clearly, N.T. Wright does not believe that the Reformation properly appealed to Paul’s texts on justification. According to him, these texts do not teach what the Reformers believed they did. And if the Bible elsewhere teaches something akin to justification (for Wright), it simply teaches the “event or process” initiating the Christian life, that of regeneration or sanctification (actualized in baptism). Wright gives no indication that he believes the Scriptures elsewhere teach the event of the active imputation of Christ’s righteousness to believers simultaneous to (but separate from) regeneration. Thus, Wright does not believe in justification as part of the ordo salutis, as we find it in Romans 8:30: “Whom he predestined, these he also called; and whom he called, these he also justified; and whom he justified, these he also glorified.”

Still, Wright believes that the work of Christ in his death somehow has a saving effect in the lives of believers at the time of regeneration, administered to them through baptism. However, Rome also asserts the same thing with its doctrine of infusion. Neither teaches the imputation of Christ’s perfect righteousness in justification.[9]

Therefore, the state of the question is: did Paul teach that justification involves the imputation of Christ’s righteousness? We hope to show that he did, and that this is indicated by his semi-eschatological doctrine of justification.

We need to get clear in our minds what Paul teaches about semi-eschatological justification. Then we can show how it requires the imputation of Christ’s righteousness to the church in union with him. Our point will be that the present semi-eschatological justification of God’s people requires the active imputation of Christ’s righteousness. And thus the essential justification of all God’s people (old and new) must also require active imputation as well.

As a result of this, in our discussion of imputation, we will sometimes talk about the relationship between the historia salutis and the ordo salutis. Historia salutis is what God does in redemptive history, and the ordo salutis is how we are identified with that redemptive history in Christ—how we are identified with Christ’s death and resurrection.

Let’s look first at the semi-eschatological justification of God’s people. We are using the term semi-eschatological as follows. As eschatology describes the final end of history, we are now talking about that eschatological finality coming into the midst of history—as Paul would say, that the end of the ages has come upon us. So we live in this time of an overlap between this age that is passing away and the age to come that is in Christ. And we are suggesting (following Vos, Ridderbos, Gaffin, and others) that the resurrection of Christ involves a declaration of his righteousness—declares Christ to be a possessor of the age to come in the heavenly places. And we too are declared to be joint possessors with him in that heavenly glory. This is the hinge of semi-realized eschatology.

We are going to suggest that there are two Old Testament backgrounds to Paul’s doctrine of semi-eschatological justification. One is that we are all fallen in Adam. Romans 5 is very clear on this. But the second aspect is that of Israel under the law. Wright and James Dunn make much of this, but misunderstand it in significant ways. Getting this background right will help us understand Paul’s semi-eschatological doctrine of justification.

The fact that we are “Fallen in Adam” is an obvious backdrop for justification (Rom. 5). But it is often downplayed in New Perspective writers. However, to properly understand Paul we need to understand how this backdrop is related to the other backdrop of Israel under the law. We will not be developing the background of “Fallen in Adam” in this article. Wright suggests this background, but he does not develop it or recognize its implications.

How can “Israel under the Law” form a backdrop to the doctrine of justification? In two ways, both positively and negatively. Positively, we can see that Old Testament saints were justified by grace alone through faith alone—as in the case of David (Rom. 4:6-8). Therefore, new covenant saints must also be justified in Christ by grace alone through faith alone. This is the positive backdrop of Israel under the law.

In the negative backdrop, we can see a relative movement from the old to the new. For the law brought the curses of the covenant on Israel. Thus, Israel was under the curses of the law and waited for the day when she would be eternally delivered from them. That is, she waited for the day in which she would receive eschatological justification in the Messiah.

We may say this has been fulfilled semi-eschatologically for us. Hence our present justification is semi-eschatological because we participate in the great day the prophets looked forward to.

But if righteous Israelites were justified by faith alone, how could they be under the curses of the covenant? What examples do we have of this? I wish to consider one such instance in Daniel 9. Daniel reflects on the exile and includes himself (a justified Israelite) when he says “the curse has been poured out on us” (v. 11); “He has confirmed his words against us” (v. 12); “all this calamity has come upon us” (v. 13); “the Lord has kept the calamity in store and brought it on us” (v. 14). Daniel (with the people) was in some sense under the curse of the law.

How is this possible; he was a justified Israelite? Our suggestion is: this is the flip side of 1 Corinthians 10 and Hebrews 6. In these passages, unregenerate people externally participate in the blessings of the covenant. We are going to suggest that in the case of Daniel we have the flip side. If a person who is condemned can externally participate in the blessings of the covenant, then a person who is justified can externally participate in the curses of the covenant. It is something of a flip reversal.

Looking at 1 Corinthians 10, we see that it was Paul’s own conviction that unregenerate people sometimes participated in the blessings of the covenant. In this passage, Paul says: “our fathers…all drank…from…Christ. Nevertheless, with most of them God was not well-pleased; for they were laid low in the wilderness” (vv. 1, 4-5). It must be that they only drank Christ externally, that is, in a way that did not give them a new heart. Otherwise, if they had a new heart, they would not have perished. For “he who began a good work in you will perfect it unto the day of Christ Jesus” (Phil. 1:6).

Thus, these unregenerate people participated in the blessings of the covenant externally, though they did not have them internally. (We are using the terms external and internal differently than we might use them of justification—as an external forensic work—and sanctification as an internal work of the Spirit.) Thus it might be better to say that these Israelites participated formally in the blessings of the covenant, but not really and essentially. Though they were actually under God’s wrath, they participated formally in the blessings that came to God’s people because of justification. But they were not justified.

Our suggestion is that the reverse took place for Daniel. He was actually justified, but he externally or formally bore the curse of the law. That is, some externally participate in blessings while actually being cursed (1 Cor. 10; Heb. 6). But others externally or formally participated in curses while actually being justified (Dan. 9). This happened to people like Daniel under the law. He was externally cursed in relationship to his inheritance in the land though he was actually justified.

When Daniel acknowledged that he was under the curses of the covenant he said: “Righteousness belongs to Thee, O Lord, but to us open shame” (9:7) and “Open shame belongs to us” (v. 8) under the curses of the covenant (v. 11). But Paul says: “I am not ashamed of the gospel for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes… for in it the righteousness of God is revealed” (Rom. 1:16-17).

Paul is not ashamed because the curses of the covenant have been lifted. Christ, though he deserved long life in the land—yea everlasting life in the eternal inheritance—has been cut off from the land of the living in an eschatological exile of shame and death. Then, having satisfied God’s eternal wrath, he was justified in his resurrection.

God has heard the prayer of Daniel. “Oh Lord, in accordance with your righteous acts, let now …your wrath turn away from your city Jerusalem” (9:16); “Oh Lord, forgive” (v. 19). And God has brought semi-eschatological justification for he told Daniel about the day he would “bring in everlasting righteousness” (v. 24) and Paul proclaims that that day has arrived in Christ Jesus and his resurrection.

This also helps us understand the words of Galatians 3:23-25. “But before faith came, we were kept in custody under the law, being shut up to the faith which was later to be revealed.” Included here is the life of Israel under the curse of the law. “Therefore the law has become our tutor to lead us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith” (v. 24). “That we might be justified by faith” clearly has an historical reference to something unique in the new covenant in some respects. This is further implied by verse 25: “But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a tutor.” “Now that faith has come,” implies that ‘now that justification by faith has come.’ There is newness in the fullness of the time with respect to justification.

Paul appears to be saying that justification has come to the new covenant people of God in a new way. He is not denying what he says elsewhere of the justification of old covenant saints as in the case of David (Rom. 4:6-8). He appears to mean that semi-eschatological justification takes the new covenant church out from under custody to the law. That is, it delivers them from the curses of the law even in the external (formal) way that Daniel and other old covenant saints experienced them.

Once again, we suggest that Paul’s statement “I am not ashamed of the gospel” is a reversal of Daniel’s shame under the curses of the covenant. If this is so, it informs Paul’s discussion throughout Romans. Justification in Romans is a reversal of the curse placed on Israel in exile. Thus, this semi-eschatological justification brings a new semi-eschatological exodus. N.T. Wright is correct as far as this latter point goes. But we will see that the redemptive-historical significance of this point supports the Reformation’s doctrine of the imputed righteousness of Christ in justification, something that Wright rejects.

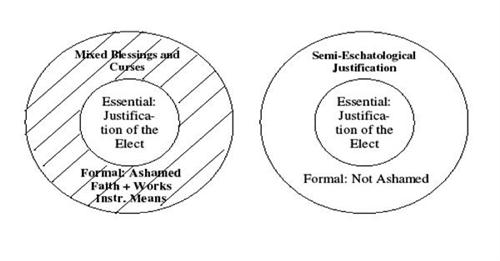

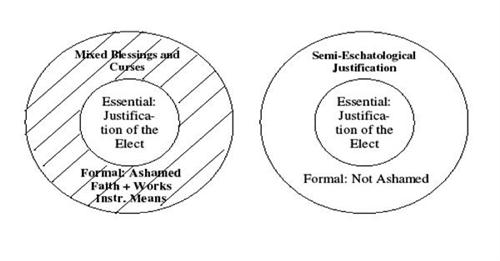

The following diagram helps illustrate the situation we have been describing. In it, the first circle represents the old covenant and the second represents the new covenant.

Recall that N.T. Wright believes that justification is simply a declaration of God. It is not a gift of God bestowed by imputation. Thus, while Wright may speak of a new exodus, his view does not do justice to the eschatological character of the new exodus in Christ. This is evident when we see that eschatological righteousness must be a gift of God because it is contrasted to the disobedience of Israel under the law.

About the new exodus, God says to Daniel: “Seventy weeks have been decreed for your people and your holy city…to bring in everlasting righteousness” (9:24). This righteousness is the reversal of Israel’s unrighteousness (vv. 7, 16, 18). Verse 25 implies that the Messiah will bring in everlasting righteousness (as in Is. 9:7). This point (along with the contrast to Israel’s unrighteousness) implies that he will give them this semi-eschatological righteousness as a gift. That is, God says there are seventy weeks decreed to bring in eternal righteousness, and then he points to the Messiah who will bring in everlasting righteousness, that is, give it as a gift.

It only remains to discover whether Paul believes this gift of righteousness (in justification) is infused or imputed to the new covenant people of God. The very fact that Paul sees this fulfilled in a semi-eschatological setting makes the answer clear. For Daniel is contrasting the sinfulness of the people (some of whom possessed the Spirit) with the perfect righteousness needed for eschatological righteousness.

Thus, the imperfect work of the Spirit even in old covenant saints did not suffice. So why would the imperfect work of the Spirit in new covenant saints be sufficient? Daniel spoke of God bringing in everlasting righteousness. Paul could not mean that this was accomplished by God’s righteousness being infused within his people, for that infusion is imperfect. And it is precisely imperfect righteousness that Daniel was decrying when he contrasted it to the future eternal righteousness to come. Daniel must have spoken of a future perfect righteousness. And this righteousness has now been fulfilled in the saints of the present semi-eschatological period. But they remain sinners. Therefore, there must be a separate work (besides regeneration and sanctification) that gives them perfect righteousness without simultaneously making them perfect. This fits with imputation which credits Christ’s perfect righteousness to sinners while they simultaneously remain sinners. As sinners, they must be imputed with the perfect righteousness of Christ in order to participate in everlasting righteousness.

Further, their semi-eschatological justification must involve the imputation of Christ’s own righteousness to them. This greater righteousness of the new age cannot simply be the declaration that they are in the covenant community (N.T. Wright), because even in the Old Testament they were in the covenant community. The prophet is not simply looking forward to a time when they will be in the covenant community again. He is looking forward to a time in which they will be participants in a greater fullness—in greater new covenant blessings. To secure this for them, God must declare them to have a righteousness that they did not possess in the old covenant (relatively speaking). Thus, he must impute to them a semi-eschatological righteousness (in terms of the formal aspect of the new covenant) as well as declare them righteous (in terms of the essential aspect of the covenant, together with old covenant saints).

Again let us ask the question, how do the curses on Israel relate to the doctrine of imputation? And how is this fulfilled? Looking ahead, we will see this fulfillment in 2 Corinthians 5:17-21.

But first, as a background to 2 Corinthians 5:17-21 (especially v. 19), let us consider Ezekiel 15:7: “I will set my face against them.” This describes what Ezekiel writes in 6:11-12: “Alas, because of all the evil abominations of the house of Israel, which will fall by sword, famine, and plague…thus I shall spend my wrath on them.” God is saying, I will set my face against my people in the covenant curses in exile, and they will have these curses—sword, famine, and plague. God uses this language for the curses of the covenant: “I will set my face against you.” That is, I will impute your sins to you, and you will bare the curses of the covenant. But, if God does not impute their sins against them they will not receive the curses of the covenant. Now, that is what has happened in Christ. Now that Christ has come God does not impute the sins of his people against them. They do not bare the curses of the covenant.

This is expressed in 2 Corinthians 5:17-19. “Therefore if any man is in Christ, he is a new creature; the old thing passed away; behold, new things have come. Now all these things are from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and gave us the ministry of reconciliation, namely, that God was in Christ, reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them.” Notice that Paul says “not counting their trespasses against them.” We are suggesting that this is a reversal of the covenant curses in which God said “I will set my face against them.” Here Paul is saying he will not count their sins against them. And what does it bring in verse 17? “Therefore, if any man is in Christ he is new creation.” ‘Not imputing their sins against them’ brings ‘new creation’. Semi-eschatological reconciliation and justification brings new creation. This is the fulfillment of what Daniel looked forward to.

As suggested, in verse 17 we can legitimately substitute the term “new creation” for “a new creature” because the term in Greek has a range of meanings. Paul will use it in Romans 1:20 to describe the act of the first creation. Here, we believe, he uses it to describe the new creation that has appeared with Christ’s reconciling work. Notice once again that the new creation is “from God” (v. 18). God has brought it to pass by means of his reconciling work in Christ. Indeed, God’s act of not counting or “not imputing their trespasses against them” resulted in the new creation. When God canceled the curses of the covenant in the formal realm of the covenant, he brought greater reconciliation (in that respect) to the new covenant people of God. He brought them greater participation in the new creation (received in smaller measure by old covenant saints), and therefore he can call it a “new creation.” This arises from not imputing their sins against them in curse and exile.

But why does God give us a “new creation” when he takes away the curses of the covenant? That is, what connection is there between this “not imputing” and the “new creation”?

We suggest that the curses of the old covenant kept Israel from enjoying the fullness of their inheritance in the land. And therefore, it kept them (at that time) from enjoying the fullness of the new inheritance in Christ Jesus—to the degree that new covenant saints would experience it. (Although we would claim that they possessed the end from the beginning already by their participation in God through the Mosaic covenant of grace. Thus, we are only talking about a relative newness here.) Their inheritance in Canaan was a foretaste and picture of heaven to come. Thus, the curses kept Israel from participating in the fullness of the heavenly kingdom to come. Once those curses were eliminated, they could participate in the kingdom to come in its fullness. Thus, when Christ bore the curses of the covenant, the kingdom came.

At first glance, this may seem to support N.T. Wright’s claim that the passive obedience of Christ was sufficient for our salvation, for this alone was necessary to reverse the curse. However, Paul’s claim that reconciliation arises from “not imputing their trespasses against them” is balanced by his assertion that Christ’s work was his “one act of righteousness” (Rom. 5:18). The background for Paul’s use of the term “righteousness” is that of the Hebrew Scriptures. It reminds us of the full active righteousness God required of his people in the Old Testament, which, for Christ, culminated in the cross. In fact, it was because his people did not attain to this full righteousness (Rom. 8:3), that they were under the curses of the law (in respect to the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant). Thus, the new creation is more than the reversal of the curse. Its very nature brings us beyond the Garden of Eden and beyond the land of Israel (contrary to Wright, who conceives of the new creation as if it were the Garden of Eden returned on a grand scale[10]). Eliminating curse alone is not sufficient. The perfect obedience that Israel failed to attain is also needed. And Christ alone has accomplished this by his active obedience, which has now been imputed to believers, bringing them the new creation.[11]

Once again, for Paul, what does semi-eschatological justification entail? The answer is that it declares God’s people semi-eschatological possessors of the final inheritance above in Christ Jesus. This is seen in Galatians 3:10-14. “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing promised to Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith.” What was the blessing promised to Abraham? It was the “the promise of the Spirit.” Therefore, the removal of the curse of the law on Israel brought the age of the Spirit. Then Paul connects the Spirit with the inheritance in verse 18. Once again, he speaks of the promise given to Abraham—and says that this was a promise of the inheritance. Thus, Paul now speaks of the promised Spirit as the promised inheritance. Clearly he implies that the Spirit is the eschatological inheritance.

Bringing together the teaching of 3:10-14 with verse 18, we may say this: Christ bore the curse of the law in order that the eschatological inheritance would come to the Gentiles. If taking away the curse brings the eschatological inheritance, this implies that the curse of the law kept the people of the Old Covenant from that inheritance. Now that this curse has been removed in Christ, the eschatological inheritance can come to the people of God.

It is an eternal inheritance, without curse in the heavenly places. It is not the present world now being transformed from its cursed state (N.T. Wright). The transcendent nature of the inheritance in Christ allows the church to possess it while living as suffering servants in this age. Since her inheritance is the transcendent Jerusalem above, the church can fully possess it even while she is persecuted in this age (Gal. 4:26-31). She experiences a semi-eschatological freedom that transcends the freedom of Israel, which was clouded with exilic bondage (in terms of the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant, Gal. 4:1-3). For the curse and bondage of the old has been reversed by semi-eschatological justification (Gal. 5:1-6), in which there is no distinction between circumcised or uncircumcised.

This greater abundance of the new covenant in terms of semi-eschatological justification is again revealed in Romans 8:1-3 and 33-37. As Romans 8:1 states: “There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus.” Paul’s use of the term “now” suggests a redemptive-historical contrast between the period of the law and the present time (as it does in Rom. 3:21 and 7:6). In it, Paul is making a relative contrast between righteous Israel under the law (Romans 7:7-25) and the new age in Christ. In terms of the formal aspect of the new covenant, there is no condemnation as there was under the formal aspect of the old covenant.[12] That this is entailed in Paul’s claim that there is “no condemnation” is further substantiated by the end of Romans 8, which forms a loose bookend to the beginning of the chapter.

In Romans 8:33-34, we read: “Who will bring a charge against God’s elect? God is the one who justifies; who is the one who condemns?” This lack of condemnation exceeds that found under the law. For under the law, “famine…nakedness…peril” and “sword” were curses of the covenant. They expressed the condemnation of the law on Israel in terms of the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant. We saw this in Ezekiel 6:11-12.

In terms of the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant, these curses kept Israel from the full enjoyment of God’s covenant love (relatively speaking). So that Paul can quote Hosea 2:23 (speaking of the new covenant) as saying, “I will call…her who was not my beloved, ‘beloved’” (Rom. 9:25). This greater love has now arrived so that Paul can say, “Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword?” Since the curse of the law has been eliminated (even in terms of the formal aspect of the covenant), these things are no longer a curse to the people of God in terms of their covenant relationship to him. Instead, in all these things they are more than conquerors.[13]

This results from the semi-eschatological justification Paul expresses in the words, “Who will bring a charge against God’s elect?” (Rom. 8:33). This reverses the words of Ezekiel 15:7: “I will set my face against them.” Again, Paul expresses this semi-eschatological justification saying, “God is the one who justifies; who is the one who condemns?” This semi-eschatological justification reverses the curse (even in terms of its expression in the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant of grace). Christ has triumphed over those things that were once opposed to God’s people (in the formal aspect of the covenant). He has brought semi-eschatological justification and it can never be reversed because it is grounded in his own resurrection-life at the right hand of God; he now presents to God a greater intercession on our behalf (Rom. 8:34).

This indicates that saints of the new covenant possess a greater union with Christ that brings them beyond the period of the law (relatively speaking). And it brings us back to the beginning of Romans 8 where Paul claims that there is “now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus.” For there he also indicates that this redemptive-historical transition took place in Christ saying: “What the law could not do, weak as it was through the flesh, God did, sending His own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and as a sin offering.” Christ accomplished what Israel could not do, and therefore he brought the semi-eschatological justification that reversed the curse and brought in everlasting righteousness (as prophesied by Daniel).

This is a bone of contention for many people who want to follow the New Perspective on Paul and who want to deny the classic doctrine of justification. They think that N.T. Wright and James Dunn provide a way of understanding justification that ties it essentially to the inclusion of the Gentiles (as we often find in Romans). They do not believe that the classic doctrine of justification does this because it claims that Jews and Gentiles are both justified in the same way in both the old and new covenants. As such, the classic doctrine of justification does not seem to imply the transition from the old to the new eras and the newly established inclusion of the Gentiles. However, we will try to show that semi-eschatological justification implies the inclusion of the Gentiles. And this semi-eschatological doctrine of justification supports the Reformation’s doctrine of justification.

First, let us briefly establish the fact that Paul’s full doctrine of justification (whatever it is) demands the inclusion of the Gentiles. Paul states in Romans 3:28-30: “For we maintain that a man is justified by faith apart from works of the Law. Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also, since indeed God who will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through faith is one.” The very fact that God justifies by faith apart from the works of the law (Paul’s doctrine of justification) implies that God will justify Gentiles who are without the law. If God did not justify the Gentiles, he would be the God of the Jews only, for only they have the law. Thus, the full expression of justification brings with it the inclusion of the Gentiles.

But the crucial point here is that it brings about a state in which God is the God of (covenant language) the Gentiles. More precisely, justification, in its full significance, implies that God is equally the God of the Gentiles as much as he is the God of the Jews. Paul’s identical language (God of the Jews, God of the Gentiles) requires this. And Romans 3:30 teaches that this unity of Jews and Gentiles results from justification.

However, the gift of justification (administered through the Mosaic covenant of grace) did not imply this. That administration (even when given to Gentiles as well as Jews) did not imply that God was equally the God of those Gentiles. There was still a covenantal distinction between uncircumcised God-fearing Gentiles and the Jews. The Jews were more fully God’s people (in terms of the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant of grace).

When Paul expresses the fact that justification ultimately implies the equal covenantal union of Jews and Gentiles in Christ, he is describing a situation that is only true (in fullness) in the new covenant era. What we have called semi-eschatological justification can account for this fact. For semi-eschatological justification legally reverses the curse (found in the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant) and destroys this barrier between Jews and Gentiles.

Looking at things from the point of view of the prophets (as we have previously), we may consider this from a different angle. If the imputation of eschatological righteousness is necessary for the Jews to receive the new exodus and its eschatological inheritance, how much more is this the case for the Gentiles? In Hosea, the more Israel becomes like the Gentiles (lo ami, “not my people”), the more she is in need of the imputation of eschatological righteousness (Hos. 2:19). Therefore, it appears that the Gentiles themselves are in need of the positive imputation of Christ’s righteousness in order to bring them eschatological justification. It would seem that the exile of Israel allowed for a situation in which Jews and Gentiles became one as ‘not my people.’ As a result, (for Paul) they can now become one people of God through semi-eschatological justification.

Dunn and Wright believe their view—that “works of the law” simply refers to Jewish boundary markers—helps explain why Paul connects his teaching on justification with the inclusion of the Gentiles. As the argument goes, if “works of the law” simply refers to circumcision and dietary laws then justification means that Gentiles do not have to keep these boundary markers to be a part of the covenant community.

Semi-eschatological justification can explain why Paul connects justification with the inclusion of the Gentiles without reducing the works of the law to “Jewish boundary markers” alone. Our suggestion is that Paul’s critique of the Judaizers is a critique of their eschatology—their desire to bring in the kingdom by force, their desire to bring eschatological righteousness by their obedience to the law. And if they believe that they can bring in eschatological righteousness by their obedience, then they believe that their present participation in that justification is also grounded in their own obedience (connecting historia salutis with ordo salutis). That is, they are at least semi-Pelagians with a pre-Reformation confusion about justification (tending toward the Council of Trent) because it fits with their eschatology.

On this Jewish view of man-made eschatology, those who would be included in the kingdom must circumcise themselves. And all uncircumcised Gentiles would be excluded. However, Paul’s semi-eschatological doctrine of justification paves the way for the Gentiles. For Paul teaches that since the eschatological righteousness of God has arrived in Christ, the kingdom has come. The eschatological inheritance has arrived in Christ. It is now semi-realized in the church. This opens the door for the Gentiles in at least several ways.

Now that the inheritance is wholly above in Christ, transcendent and eternal, it is not tied to any particular geographical location. Thus, Gentiles can participate in this transcendent inheritance without connecting themselves to the land of Israel through circumcision. As we have shown, this transcendent inheritance above is a result of semi-eschatological justification. Therefore, the inclusion of the Gentiles (made possible by this transcendent inheritance) is also a result of semi-eschatological justification.

The curses of the old covenant separated most uncircumcised Gentiles from any participation in the covenant-life of Israel. Now that Christ has borne the curses and broken down the dividing wall of partition, the gospel has gone to the Gentiles, and they now have equal access to the presence of God in Christ (Eph. 2:14).

Even uncircumcised God-fearing Gentiles in the old covenant did not have full access to the privileges of Israel. For the curses of the law embodied in the purification rites kept them from it. This was reversed when Christ broke down the dividing wall, making them one body. This fits with what we have seen above in Romans 3:28-29. Semi-eschatological justification requires the inclusion of the Gentiles into one body so that God is equally the God of the Jews and the God of the Gentiles.

Like the Jews, the curses of the old covenant kept the Gentiles from full semi-eschatological participation in the inheritance above. Now that Christ redeemed them from the curse of the law, they can participate in this heavenly inheritance. Thus, semi-eschatological justification implies the inclusion of the Gentiles.

Thus, Paul’s view of semi-eschatological justification does greater justice to the relationship between justification and the inclusion of the Gentiles. This can be illustrated from Galatians 3:23-4:7.

Looking at Galatians 3:23-26, Paul writes: “But before faith came, we were kept in custody under the law, being shut up to the faith which was later to be revealed. Therefore the Law has become our tutor to lead us to Christ, that we might be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a tutor, for you are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus.”

Before looking at this text, we should note that many New Testament scholars do not recognize the implications we will suggest. For, in our opinion, they wrongly restrict the “we” of these passages to Jewish believers. To justify their view, numerous New Testament scholars point to the fact that in 1 Corinthians 9:20-21, Paul restricts the phrase “under the law” to Jews, implying that Gentiles are not under the law. Then they apply this interpretation to Galatians 3:23-4:7, suggesting that Paul is here restricting his discussion to Jewish Christians (i.e., only they were once under the law and so redeemed from it). Following this, they conclude that when Paul stated “we were kept in custody” and “we are no longer under a tutor,” he was referring to Jews only. For only Jews were under law.

However, we would suggest that Paul’s distinction in 1 Corinthians 9:20-21 is one he makes when contrasting Jews and Gentiles. But when he discusses their common plight under the curse of the law, he can speak of Gentiles as also under law.

The flow of thought in Galatians 3:23-26 seems to indicate this. For right after saying “we are no longer under a tutor,” he gives the reason—“for you are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus.” This “you” certainly includes Gentile believers as we find in verse 28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek…for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Thus, he here speaks to the whole church, Jews and Gentiles alike, when he states, “you are all sons of God” (emphasis mine). Further, since there is every indication that the “we” referents and the “you” referents are the same, the “we” referents must also refer to Gentiles. Thus, “we were kept in custody” describes Gentiles as well as Jews.

In any event, it is clear to most that the “we” passages must include the Jews. And this makes Galatians 3:23-29 most interesting. For it implies that Jews (in Christ) have been justified in a new way since his coming. It implies semi-eschatological justification. We can see this by first recognizing that verses 23 and 25 describe faith as coming. This coming of faith is not simply the coming of faith to the individual soul (although this is implied as well). Instead, it describes the historical coming of faith in a new way with the historical arrival of Christ and his work.

This can be seen from the fact that this coming of faith resulted in greater equality among the people of God than existed under the old covenant. Under the period of the law, there were distinctions among God’s people in terms of their inheritance rights in the land. Even God-fearing Gentiles did not possess the inheritance rights of Jews. Also the male, as opposed to the female, usually possessed the inheritance. And finally, the free man possessed his inheritance while the slave worked for another and contributed to his property.[14] Paul is here suggesting that the coming of faith is the coming of the new era, in which these distinctions no longer exist.

Connected with this historical coming of faith is the historical coming of justification. “Therefore the law has been our tutor to lead us to Christ, that we may be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a tutor” (Gal. 3:24-25). Here we can see that Paul intimately connects the coming of faith with the coming of justification. The period of tutelage under the law awaits the coming of faith and justification in the new era. As if to say, justification comes in a new way after the historical accomplishment of Christ’s work. This suggests Paul’s doctrine of semi-eschatological justification: that justification came to the people of God in a new way after Christ’s resurrection.

This fits with what we have previously recognized, that this semi-eschatological justification involved the reversal of the curse expressed in the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant. For the tutelage of the law (seen from the point of view of the contrast between the old and new covenants of grace) was not absolute, but only relative. It dealt with the visible blessings of inheritance in the old covenant. And these visible blessings were still mixed with the curse of the law.[15] But now in Christ Jesus, semi-eschatological justification has reversed the curse, making us full and equal “heirs” (Gal. 3:29) of all that is our inheritance in him.

Now we come full circle to our claim that the “we” passages include the Gentiles. If semi-eschatological justification brings something new to the Jews, it also brings something new to the Gentiles (who are included in the “we” passages). This has already been glimpsed in the Gentiles’s equal participation in the inheritance in Christ. Thus, Galatians 3 suggests that semi-eschatological justification opens the way to the full participation of Gentiles in all the covenant blessings of God. Semi-eschatological justification implies the inclusion of the Gentiles. The New Perspective does not have a corner on this market.

By understanding semi-eschatological justification, we can see how it has reversed the situation of both Jew and Gentile—for it has reversed the curse of the law that kept them both from the fullness of the eschatological inheritance.

The reversal of this curse brings a new exodus. However, as we have seen from the prophets, the reversal of the curse requires the positive imputation of righteousness. This is not lost on Paul—who expounds the freedom of the Jerusalem that is above—a Jerusalem that is more than just the earthly Jerusalem without curse.

The fact that Jews and Gentiles are both redeemed from the curse of the law shows us how the ordo salutis and the historia salutis are interrelated. We note this in response to Wright, who subtly undercuts the ordo salutis by reference to the historia salutis. When we consider the movement of the first Jewish Christians from the old to the new covenant, the historia salutis is primarily highlighted. But when we consider many of the early Gentile converts to Christianity, the ordo salutis is highlighted. For they were not previously part of the covenant people of God. Thus, most of them never lived like Daniel—being justified, yet externally under the curses of the covenant. They did not move from one redeemed state to a greater one. Instead, they moved from a completely unredeemed state to that of semi-eschatological justification. As a result, the ordo salutis is brought to our attention. The movement from wrath to grace in the life of these individuals is highlighted. This is the case even though it was the new redemptive historical situation that allowed them to be participants in the ordo salutis. That is, they come to participate in the new semi-eschatological justification in Christ, but they do so by moving from a situation of complete wrath to grace. So they must be coming from that at a point in their lives. For their new redeemed state is absolutely different from their previous unredeemed state.

As a result, the ordo salutis is an essential part of the historia salutis for the Gentiles. When the Gentiles are brought to participate in semi-eschatological justification they are united to the historia salutis represented in it at a particular point in their personal lives (ordo salutis). And this is also true of all Jewish Christians who were regenerated by Spirit for the first time after Christ’s resurrection.

You now may be wondering—if we are proving the need for imputation based on semi-eschatological justification, does this have any implications about the justification of Old Testament saints? Did their justification require imputation? We strongly affirm that it did. For eschatological finality determines Paul’s way of understanding the fundamental nature of God’s grace in the old covenant. The demonstration of God’s eschatological righteousness is the basis for the justification of Old Testament saints whose sins he passed over in his forbearance (Rom. 3:25). This then informs our understanding of the way in which Old Testament saints were justified (Rom. 4:6-8). Their justification before God’s throne must have been by way of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness. For Paul then uses David’s justification as an example of our semi-eschatological justification in Christ.

Thus, their justification gave them all the benefits of justification articulated in the Westminster Confession of Faith, although it did not then deliver them externally from the covenant curses as semi-eschatological justification does now for new covenant saints. However, in their justification, they possessed the end from the beginning—anticipating final eschatological justification in Christ. Thus, their life was a foretaste of the final eschatological end of the ages, and in that foretaste they participated in the end from the beginning, making them final participants in the resurrection of Christ and final eschatological justification in him.

In conclusion, we have attempted to show that semi-eschatological justification involves the forensic imputation of Christ’s perfect righteousness to new covenant saints in the formal sphere of the new covenant. It is also the foundation of the justification that both old and new covenant saints receive through the essential nature of the covenant of grace. For this essential grace in all periods of redemptive history is an intrusion of the eschatological justification of Christ, declared to be his in his resurrection.

Therefore, we have concluded that the justification of all God’s people throughout redemptive history must also be by forensic imputation. For it must bear the imprint of semi-eschatological justification. That is, just like semi-eschatological justification, the justification of old and new covenant saints alike (in relation to the essential nature of the covenant of grace) is grounded in their union with Christ. As such, it must involve the imputation of Christ’s righteousness (contrary to N.T. Wright).

Further, we have attempted to show that Christ’s righteousness, declared to be his in his resurrection, is the culmination of both his active and passive obedience to the law of his Father. Therefore, it is this righteousness (both of Christ’s active and passive obedience) that must be imputed to Christians, that they might be the righteousness of God in him.

In these ways, Paul’s doctrine of semi-eschatological justification requires the Reformation’s doctrine of justification, as the imputation of Christ’s active and passive obedience to believers. Far from detracting from the Reformation’s doctrine, a redemptive-historical assessment of it both supports and enriches it. And it leads the people of God to glory only in Christ Jesus, his coming, his resurrection, and their participation in his righteousness alone. Soli Deo Gloria.

[1] This article is a revision of an address given at the 2005 Kerux Conference, entitled “Paul and Eschatological Justification with a Critique of Dunn and Wright.”

[2] My thanks to the editor of this journal who, after I delivered this address, suggested the term “formal” instead of the terms “external” or “visible” to describe this aspect of the new covenant.

[3] When we speak of justification in terms of the essential nature of the covenant, this is not to be confused with the view of Andreas Osiander, who taught that justification involved the essential righteousness of God. Here we are simply using the term “essential” to describe the “essence” of the covenant of grace, which is identical in both the Mosaic administration of the covenant of grace and the new covenant. And we are contrasting this to the “formal” aspect of each covenant, which represents their unique administrations.

[4] Rome (unlike Wright) believes that this declaration will only occur in the future. She does not believe that baptism is already a declaration of future justification. She only believes that baptism (as an infusion of grace) is the first stage of justification. However, (in Rome’s opinion) the initial justification that takes place in baptism might not be followed by final justification (in the case of those who have committed mortal sin). Therefore, she does not believe that this infusion is a declaration (before the time) of final eschatological justification. According to our discussion, she does not believe that the second aspect of justification (as a declaration of righteousness) takes place in baptism. We would think (though this is not clear to us) that Dr. Wright would have to disagree with Rome’s claim that the initially justified might still be damned. For Dr. Wright believes that baptism is a foretaste of final eschatological justification (which we presume means it cannot be reversed). If, on the other hand, Dr. Wright agrees with Rome on this point, then even he does not believe in what we have called the second aspect of justification. Instead, we would need to modify our claim, stating that while Wright rejects the first aspect of justification altogether, he gives lip service to the second aspect of justification. This second aspect he then reduces (on this construction of his view) to the declaration that one is presently in the covenant community, while tomorrow one may not be (which is little different from Rome).

[5] N.T. Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity? (1997) 115.

[6] Ibid., 116.

[7] Ibid., 116-17.

[8] Ibid., 117.

[9] Wright further departs from the Reformation in his analysis of Christ’s objective historical work of redemption (the historia salutis). Wright does not believe that Christ’s active obedience to the law (during his own lifetime) contributes to our salvation. Nor does he recognize that Christ’s active obedience culminated in the righteousness Christ now possesses in his resurrection life, a righteousness that goes beyond Adam’s righteousness in the Garden of Eden. Even though Wright refers to Christ’s justification in his resurrection, he essentially reduces its background to Christ’s passive obedience. Basically, for Wright, only Christ’s passive obedience of suffering on the cross contributes to our salvation.

[10] Actually, N.T. Wright’s view does not really do justice even to the fact that Christ has eliminated the curse from the inheritance. For Wright, like many Restorationists (who seek to restore the garden paradise of God in this world through a process of Christian activity), assumes that this present world is the inheritance of God’s people. The goal of Christian activity involves eliminating the curse from this present world (as the inheritance). However, Paul teaches that the curse has already been eliminated from the inheritance. Therefore, Dr. Wright (together with other Restorationists) is at odds with Paul’s doctrine of semi-eschatological justification—even in terms of the imputation of Christ’s passive obedience. His Restorationist view is a failure to recognize that the kingdom has come semi-eschatologically. And since semi-eschatological justification is for Paul the fountainhead, of which the justification of Old Testament is an intrusion, it is no wonder that Dr. Wright and his disciples also deny the classic Reformation doctrine of justification as applied to all the people of God (old and new).

[11] To put it another way, we are suggesting that Paul’s conception of the “new creation” as semi-eschatological mitigates against Wright’s claim that Christ did not merit active obedience to be credited to our account. Here we will argue that the nature of the righteousness that God now imputes to Christians semi-eschatologically must be equal to the righteousness he will give Christians internally in the final eschatological state. Since the internal righteousness of the final eschatological state depends on Christ’s active obedience, so also, the present imputation of Christ’s righteousness (semi-eschatologically) must depend on his active obedience. To begin, we will consider the nature of the “new creation”. The eschatological character of this “new creation” implies that it is eternal. It can never be reversed in the way the first creation was reversed (by the fall). If Christ only suffered to reverse the effects of the fall (as Wright implies), then he would only return Christians to a state similar to that of the Garden of Eden. This garden state (even in its final “eschatological” form) would possess all the same qualities as those of the Garden of Eden except those earned for it by Christ’s passive obedience. Thus, it would be one in which transgression was possible—even if the guilt of these transgressions had already been forgiven by Christ’s passive obedience. For what in Christ’s passive obedience rewards Christians with the gift of perfect future obedience? However, for Paul, such a state is out of the question. The eschatological nature of the new creation will bring people into a new state in which they cannot fall. And this is only possible if Christ performed the perfect obedience that God once required of Adam. Only by accomplishing this active obedience could Christ give to believers their own perfect obedience in the final eschatological state. Pure innocence (and lack of guilt) did not earn Adam the final eschatological state or else it would have been his reward within seconds of his creation. No, Adam was required to perform positive active obedience in order to attain to a future eschatological state in which he could not fall. This he never accomplished. However, the arrival of the final eschatological state (in which Christians cannot sin) will manifest that Christ has already accomplished this perfect active righteousness. He has brought Christians to a state that Adam did not have. He has actively accomplished what the first Adam failed to do. Thus, the internal righteousness of Christians in heaven will reveal that Christ has earned this for them by his active obedience. It is this final eschatological state that has already been manifested semi-eschatologically. For Christians to participate in the eschatological state even now (semi-eschatologically) they must be imputed with this same eschatological righteousness in its complete nature—as both passive and active obedience.

[12] Paul is simultaneously saying that there is no condemnation (absolutely speaking) for those in Christ Jesus. As I have suggested elsewhere, Paul often uses the same words to express both a relative contrast between the old and new covenants and an absolute contrast between life in Christ and that of absolute curse in bondage to this age. See my “Paul and the Law,” in Kerux: The Journal of Northwest Theological Seminary 17/2 (September, 2002), esp. 37-38.

[13] Once again, this is contrary to Wright’s Restitutionist perspective, in which the forward march of the kingdom is ultimately found in the triumph of earthly blessedness for the church and world. It may be asked, if Paul is speaking of a new reality of the kingdom, why does he quote a psalm from the Old Testament to support it (Rom. 8:36)? We would again suggest that Paul is only speaking of a relative contrast between the old and new covenants. Thus, the essentially gracious nature of the Deuteronomic provisions bore the seeds that would lead to the restructuring of its formal lines of development. The incompleteness of these formal Deuteronomic provisions (and the need of Christ’s coming kingdom) became more and more evident with the progress of Old Testament redemption and revelation. Throughout her history, the national blessedness of Israel both progressed and regressed (in terms of the formal relation of the Mosaic covenant). In this way, God revealed that the fullness of his kingdom had not yet arrived and could only do so by his direct hand in both the essential and formal aspects of the new covenant. As in other respects, the Psalms portray this progression and regression when they more clearly unfold the blessing of the righteous in the midst of curse and oppression, thus more fully anticipating the time when God’s blessings would overcome the curse in the midst of suffering in union with Christ (in his death and resurrection). Psalm 44 appears to represent a further revelation along this line of development. It was probably written at a time when the people as a whole were faithful (vv. 17-22) and yet God turned them over to their enemies. As a result, some interpreters believe this psalm represents an exception to the general Deuteronomic perspective, in which God promises to prosper the obedient nation but to send his unfaithful people into exile. In this way, Psalm 44 seems to look ahead, stretching our eyes (through a glass darkly) beyond the blessings and curses of the old covenant administration. Regardless of any mysteries that still surround this psalm, we believe that when all the data is taken into consideration (including that already examined in Rom. 8:33-37), it is sufficient to persuade us that Paul was arguing in these verses that the new covenant administers a greater expression of ‘no condemnation’ in terms of the formal aspect of the covenant. Again, we speak here only of degrees, for even the formal aspect of the old covenant was primarily gracious, not condemnatory. And this formal expression of grace was dependent on the perfect justifying verdict found in the essential nature of the Mosaic covenant. Our only claim is that the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant (grounded in this grace) was also mixed with visible curses that have now been reversed in the new covenant.

[14] This theme of the relative contrast between the old and the new inheritance occurs throughout Galatians 3, from Paul’s quotations in 3:10-14 to the explicit mention of the eschatological inheritance in 3:18. That this theme continues till the end of the chapter is seen in Paul’s reference to “heirs according to promise” in verse 29.

[15] Paul further suggests this in other parts of Galatians 3-4. First, we note Galatians 4:4-5 where Paul teaches that being under the law required redemption. For once this redemption was accomplished, something was removed that finally allowed the new period of sonship to arrive (4:4-6). Second, Galatians 3:13-14 teaches that when the curse of the law was borne by Christ, this resulted in something new in the history of redemption, namely, the arrival of the semi-eschatological inheritance of the Spirit, which itself opened the way for full participation by the Gentiles (v. 14). Since this removal of the curse resulted in a relative contrast between the old and the new eras, we suggest that it involved the removal of the curse in terms of the formal aspect of the Mosaic covenant. This is further suggested by Paul’s quotations in the immediate context (Gal. 3:10-13). At the same time, we affirm that these same words (vv. 13-14) also refer to Christ bearing the absolute curse his people deserved as members of fallen humanity. The same gospel is for both Jews and Gentiles alike.