[K:NWTS 24/3 (Dec 2009) 3-152]

For the past thirty years, a shift in Reformed covenant theology has been percolating under the hot Southern California sun in Escondido. Atop the bluff of a former orange grove, a quiet redefinition of the Sinaitic covenant administration as a typological covenant of works, complete with meritorious obedience and meritorious reward has been ripening. The architect of this paradigm shift was the late Meredith G. Kline, who taught at Westminster Escondido (WSCal) for more than 20 years. Many of Kline’s colleagues, former students (several now teaching in Escondido) and admirers (Mark Karlberg, T. David Gordon, etc.) have canonized his novel reconstruction of the Mosaic covenant—it is “not of faith”, but of works and meritorious works at that, albeit ‘typological’. What may now be labeled the “Escondido Hermeneutic” or “Kline Works-Merit Paradigm” has succeeded in cornering an increasing share of the Reformed covenant market in spite of its revisionism and heterodoxy. This newfangled paradigm has managed to fly beneath the radar of most Reformed observers, in part because of the aggressively militant demeanor and rhetoric of its advocates and defenders. Especially vitriolic have been attacks by the Kline acolytes upon Norman Shepherd and Richard Gaffin.

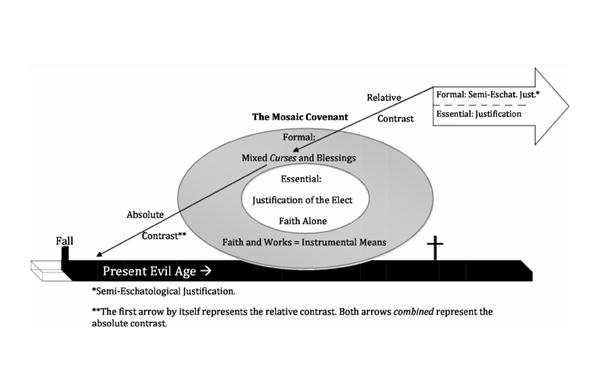

Now comes the book under review and what has flown beneath the radar is on the table with the sponsorship of WSCal—which necessarily includes the members of its Board of Directors, Faculty and student body (“We are also thankful for the institutional support we received from Westminster Theological Seminary in California,” “Acknowledgements,” ix). We have now, in print, a volume of essays dedicated to the revisionist Kline paradigm, articulated on all the controverted points to define the Mosaic covenant “in some sense” as a covenant of works. But not just a covenant with “thou shalt” and “thou shalt not” works codified; rather a covenant which “republishes” the Adamic covenant of works at Mt. Sinai. In other words, a major thesis of this book and the Kline reconstruction of the Mosaic covenant is a regression (as opposed to a progression) in the history of redemption—a regression to a prelapsarian works covenant. Kline and the advocates of the “Escondido Hermeneutic” consider Israel at Mt. Sinai as a re-embodiment of Adam before the Fall. That is, Mosaic Israel is in a covenant relationship with God as a probationary new Adam in the wilderness as the probationary old Adam was in the garden. Mosaic Israel (corrupted and polluted with Adamic transgression—for all are guilty of total depravity and total inability after Adam’s Fall, even all Israel under Moses at Sinai), according to this book’s theory of the covenant at Sinai, is to be viewed in the same light as sinless Adam in the garden—undergoing a desert probation on the basis of works and as capable of the (meritorious) reward of passing that probation as prelapsarian (unfallen) Adam in the garden.[2] Readers of this volume must not minimize the parallel between sinless Adam in the garden and Israel at Sinai; the authors and “support”ers of this book do not want you to misunderstand this fundamental thesis of the Klinean “Escondido Hermeneutic”. Repeatedly, the principle is enunciated, defended and made a test of orthodoxy in these pages. Even those essays which may seem unengaged with the major thesis (Waters) must be regarded as endorsing the thesis (“…the contributors…agreed to participate in this project…who submitted…their many theological insights into the Mosaic covenant,” “Acknowledgements,” ix).

To clarify this Israel-as-a-typological-new-Adam thesis, the book contains a pivotal essay with the subhead “Entitlement”[3]. An entitlement is that which is due or owed to a subject because the subject is worthy of that entitlement. Deserving the benefit of an entitlement, the recipient is owed that privilege because the one granting the entitlement has pledged it as an obligation on his part to reward the status of the recipient on their part.

In other words, entitlement theology is works-merit theology.[4] And that works-merit paradigm for Israel under the Mosaic covenant is vigorously defended by this book. That Israel, on account of its inclusion in Adamic depravity and inability, is incapable of works-merit is glossed over. According to the inspired apostle (Rom. 5:12ff.; 1 Cor. 15:44, 45), there are only two persons in the history of redemption capable of works-merit: the prelapsarian protological Adam and the postlapsarian eschatological Adam. In between Adam the first (protos) and Adam the last (eschatos) no lapsarian human or nation of humans is capable of works-merit because every lapsarian (fallen) human or nation of humans is in a state of works-demerit. And that, of course, means that all such fallen humans and nations between Adam and Christ require grace to remit their demerit. Grace after the Fall, grace for Abraham, grace for Israel at the Exodus, grace for Israel at Sinai in the wilderness—grace, grace, always and ever the gracious covenant of God, in Christ, by his Spirit to the undeserving, to those entitled only to damnation, to those whose works are incapable of any merit, to those infected by Adamic demerit and whose works are paid with the wages of sin, which is death.

The construction of merit in the work under review skews and deconstructs this Biblical and Pauline paradigm. Deconstructs it in the interest of a novel hermeneutic which misreads primary documents,[5] perverts the plain teaching of the Word of God, ignores the Augustinian-Calvinist tradition on grace and merit, translates all mention of a covenant of works at Sinai in previous Reformed theology into a Kline works-merit paradigm in spite of the fact that those writers never mention “covenant of works at Sinai” as a re-imaging of Israel as a prelapsarian Adam figure; pretends that the history of exegesis of Lev. 18:5 and related passages is only accurate where it agrees with their perverse exegesis.

We conclude that “in some sense” this book defends the thesis that Israel at Sinai was capable of works righteousness. Because the thesis of this book is Meredith G. Kline’s antithesis between the Abrahamic covenant and the Mosaic covenant (the Mosaic is not substantially or essentially a covenant of grace, contra Abraham), we can only conclude that Israel at Sinai is “in some sense” capable of works righteous and able to earn rewards from God on the meritorious ground of this works righteousness.[6] These merited blessings may be temporal, but they are works righteous blessings and deserving of those meritorious (temporal) blessings. Hence to deconstruct the Mosaic covenant as “in some sense” a covenant of works means for the Klinean advocates of the “Escondido Hermeneutic” that Israel in the Mosaic era was capable of works righteousness and meritorious reward. And that, interested reader, is not Reformed orthodoxy—it is not even Protestant orthodoxy. It is dangerous heterodoxy and confusion.

The merit formulations in this book are both dangerous and irresponsible. We are sounding an alarm to the Reformed community—this book is a revisionist redefinition of historic Reformed covenant theology. And it is not coincidental that Meredith G. Kline, T. David Gordon and others have called for the revision of the chapter on covenant theology (chapter 7) in the Reformed Confession of Faith composed at Westminster Abbey in the 17th century. The revisionist thesis of this book is the key to a larger and more revolutionary hidden agenda—the revisionist redefinition of historic Reformed covenant theology and the reimaging of the Reformed Confessions in the Klinean paradigm of the “Escondido Hermeneutic”.

We begin with some fundamental principles of the Augustinian-Calvinistic system. Failure to understand these is, in our opinion, an essential aspect of the deviation which is endemic to the book under review. This deviation is the “elephant in the room” of this book, i.e., the presupposition which underlies the book’s thesis. Bryan Estelle clearly expresses it in his endorsement of the following statement by Jacob Milgrom: [Lev. 20:7-8 makes clear that] “Israel can achieve holiness only by its own efforts. YHWH has given it the means: Israel makes itself holy by obeying YHWH’s commandments” (116). Estelle further affirms that “in the context of the Old Testament itself, there is often the assumption that the law can be kept in some measure and indeed has been kept by certain generations, such as the generation of Joshua and Caleb” (118, n.45). Estelle and the authors of this volume affirm a typological works-merit paradigm. Estelle, in the quotes above, places that thesis plainly and succinctly before us: Israel is capable of “achie[ving] holiness only by her own efforts”; she “makes [her]self holy by obeying YHWH’s commandments,” showing “that the law can be kept in some measure and indeed has been kept by certain generations” of the OT. These remarks, in support of the works-merit pattern, raise the question of human ability as formulated in the classic Augustinian-Calvinistic paradigm.[7] Hence, we begin with a summary of that paradigm.

The umbrage with which the arch-heretic, Pelagius, greeted Augustine’s remark (“[Lord] give what Thou commandest, and command what Thou wilt,” Confessions, 10.29.40[8]) lays down the gauntlet on the fundamental antithesis between pagan anthropology and Christian anthropology. In his “Letter to Demetrias”, Pelagius ridiculed this Augustinian dictum: “We assert that [the Lord] does not understand what he made and does not realize what he commands. We imply that the creator of humanity has forgotten its weakness and imposes precepts which a human being cannot bear . . . The just one did not choose to command the impossible; nor did the loving one plan to condemn a person for what he could not avoid.”[9] You will note that Pelagius, as all pagans, declares that what God commands, the creature is able to perform (‘Command what Thou wilt and I am able to do it’). In other words, “ought” implies “can”.[10] For Pelagius (as for all paganism), if God commands that the creature ought to do something, this is a clear demonstration that the creature is able to do the thing God has commanded him to do. For example, if God commands you to love the Lord your God with all your heart, mind, soul and strength, you are able to do this. Or if God commands you to believe on the Lord Jesus Christ so that you will be saved, you are able to do this. The sinful creature is able, according to Pelagius, to perform the mandates of God. That is, performance of a hortatory or ethical command from God is fully within the ability of the sinful creature. “Do this” (says God to the sinner) “and you shall live.” And the sinner, according to Pelagius, replies, “Since you command me to do it Lord, I am able to do it and live.” For Pelagius, the demand of performing the condition of God’s command means the sinner is capable, in his sinful condition and nature, of performing the condition demanded. It is necessary to understand Pelagian or pagan anthropology in the matter of sinful man’s ability to perform divine mandates, to comply with divine conditions, to be able to do what God commands, in order to understand the Pelagian or pagan concept of merit, i.e., human deserving, even as a sinner, on the basis of performing what God commands. One will never understand Augustine on grace and merit, let alone the apostle Paul or John Calvin and the Reformed tradition for that matter, if one does not understand the Pelagian doctrine of human ability even in sinners to perform divine commands and, as a result, earn rewards (merits), earthly, temporal and eternal from God.

Thus, the conflict between Augustine and Pelagius over whether “ought” does indeed imply “can”; whether God’s commands require God’s grace for performance of those commands or whether human ability is sufficient for performance of God’s will; whether a sinful man, even a redeemed sinful man, is able to indebt God to his performance of the divine will as a meritorious ground of reward[11]; in short, whether what God requires, he himself must perform by his grace, i.e., the Lord God who requires the condition, must himself supply the condition by his grace[12]—this conflict is the bedrock of the biblical doctrine of God and man, of grace and merit, of ethical demand and human performance. The proper understanding of biblical-Pauline-Augustinian-Calvinistic anthropology and soteriology is reflected in the primary documents of the Augustinian-Pelagian controversy, as well as the Calvin-Pighius controversy. Failure to read and understand these texts will leave the student, the seminarian, the pastor, the theologian unprepared for the development of Augustinianism in Calvin, the Puritans, the Westminster Divines, Francis Turretin, Jonathan Edwards, Charles Hodge, etc. and the development of Pelagianism in Julian of Eclanum, John Cassian, James Arminius, John Wesley, Charles Finney, Horton Wiley, etc. The student seminarian, pastor, theologian who has not worked through the primary documents of the Augustinian-Pelagian controversy is unprepared for the discussion of grace, merit and free will. This discussion is fundamental essentially; these documents must be assimilated passionately.

The documents in question include: Augustine, Confessions; his works against the Pelagians—On Grace and Free Will (NPNF1, 5:443-65); On the Predestination of the Saints (NPNF1, 5:497-519); On the Spirit and the Letter (NPNF1, 5:83-114); On Nature and Grace, against Pelagius (NPNF1, 5:121-51); Letter 194 To Sixtus (Augustine, Letters 165-203 [Fathers of the Church/FC, v. 30 (1955)] 301-32); On Rebuke and Grace (NPNF1, 5:471-91); De Questionibus Ad Simplicianum (“Questions to Simplicianus,” in Augustine: Earlier Writings [Library of Christian Classics/LCC, 1953] 376-406); On the Grace of Christ and Original Sin (NPNF1, 5:217-55). And from the pen of Pelagius: his “Letter to Demetrias”; Commentary on Romans (1993); his Four Letters (1968) as well as another edition of his Letters which contains 18 epistles (1991); and his voluminous comments quoted in Augustine’s works. From the pen of John Calvin: The Bondage and Liberation of the Will (1996); On the Eternal Predestination of God (available as Consensus Genevensis, in James T. Dennison, Jr., ed., The Reformed Confessions of the 16th and 17th Centuries in English Translation: Volume 1, 1523-1552 [2008] 693-820).

We continue with Augustine’s famous declaration which provoked Pelagius’s negative reaction: “[Lord] give what Thou commandest, and command what Thou wilt.” Augustine speaks here as a sinner, fallen and corrupt in Adam. He behaves as every sinner behaves in accordance with his Adamic nature. Augustine was personally intensely aware of his miserable sinner nature. Thus, God’s commands, God’s moral mandates, God’s ethical conditions found him in his sinful estate/condition unable to perform what God commanded. His total inability was evident to and in himself. The condition God demanded, as by right of being Creator-Lord, was his just prerogative; the condition God demanded, sinful Augustine as sinful everyman, was not able to perform. The sinner was not able to obey God’s command; the sinner was not able to perform the condition demanded by God. Therefore, the God who demanded the condition had himself to perform the condition which he required in the sinner.[13] Every sinner from Adam to the end of the world was unable to perform the condition God demanded. The sinner Adam was unable; the sinner Noah was unable; the sinner Abraham was unable; the sinner Moses was unable; all Israel at Sinai were sinners and unable to perform God’s conditions, thereby equally unable to merit God’s blessing through their obedience; the sinner David was unable; the sinner Paul was unable: every sinner at every stage and period of the history of redemption was under Augustine’s paradigm—“Command what you will, O Lord and give what you command.” From “walk before me and be thou perfect” (Gen. 17:1) to “do this and you shall live” (Lev. 18:5) to “go and sell all your possessions and give to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven” (Mt. 19:21)—all conditions demanded by God implied no ability in the sinners who were obligated by the conditions to fulfill or perform them. The passages show man his duty, not his ability. At every period of the history of redemption, every sinner was under divine obligation to perform the condition of God’s demands; but at every period of redemptive history, every sinner was unable to perform the condition of God’s demands.[14]

In support of this paradigm, Augustine marshaled three principle texts of Scripture: 1 Cor. 4:7; Rom. 11:35; Job 41:11. “What do you have that you have not received” (1 Cor. 4:7). The sinner has nothing except what he has received as a gift from God. No sinner has life from God which has not been received from God as a gift. There is nothing in what a sinner has that could be called merit (merit as what is due to the sinner from God because the sinner performed God’s condition and earned God’s reward) whether temporal or eternal, typological or eschatological. Such a paradigm contradicts what Paul writes in 1 Cor. 4:7. You, O sinner, have nothing—nothing earned by merit, by reward, by the ground of your obedience. You, O sinner, have anything you have from God by gift, by his favor, by his grace, by his performance of the condition in you. O sinner, there is in your sinful self no meritorious ground of reward from God either in this temporal life or in eternal life, for you have nothing that you have not received from God as a gift of his unmerited, undeserved, unearned grace. 1 Cor. 4:7 completely repudiates any merit paradigm for sinful sons of Adam and daughters of Eve, whether east of Eden, gathered at Hebron, camped at Mt. Sinai, basking in David’s Jerusalem or sojourning in the church of Jesus Christ. The fundamental antithesis in anthropology from Adam to the consummation—the essential, categorical antithesis in mankind’s history in every era from Adam to the new heavens and new earth is merit versus grace. Augustine does not craft a relative contrast between human merit and divine grace; he demonstrates from the Scriptures an absolute antithesis between merit and grace. If I may fast forward to a 20th century Augustinian, Cornelius Van Til, the antithesis in Christian theology is fundamentally merit versus grace. These are two absolutely antithetical categories and all claimants to Van Til’s legacy ought to know, embrace, teach and preach this fact. Listen to Augustine: “grace . . . is not bestowed according to man’s deserts; otherwise grace would no longer be grace. For grace is so designated because it is given gratuitously” (On Grace and Free Will, 21.43; NPNF1, 5:463). Gratia gratis data (“grace given gratis”)—grace given gratuitously, freely, unmeritoriously: that is the hallmark of the biblical, Pauline, Augustinian, Calvinist paradigm.

“Who has given to [God] that it shall be given to him again” (Rom. 11:35). What sinner from Adam to Noah to Abraham to Israel to Paul will give to God obedience, conformity to righteousness, performance of legal works—what sinner will give these to God and God will, in turn, give to him a reward? No sinner from Adam to Noah to Abraham to Israel to Paul will give to God so as to receive from God, on the meritorious ground of that sinner’s righteousness, a reward in this life or the life to come, for “who has given to me [says the Lord] that I should repay him?” (Job 41:11)? Who among the sinners of the world in the wide range of the history of redemption—who has given to me, the Lord, obedience which I should repay; who has given to me, the Lord, righteousness that merits my paying him with my favor; who has rendered to me deeds of merit and worth that I should reward him by repayment with my blessings either temporal or eternal? Who? Who has merited at my hand that I should repay him? No man; no one; no sinner in any era in the history of redemption where sin pervades sinful men, women and children.

All sinful men, women and children in every era of the history of redemption are a massa perditionis (“mass of perdition”), a massa damnata (“damnable mass”), a massa peccati (“mass of sin”). All descendants of Adam are a mass of perdition, a damnable mass, a mass of sin. This is Augustine’s doctrine of original sin and its consequences based upon Rom. 5:12-21 especially, but also formulated from the antithetical paradigm of grace and merit. The condition of mankind by nature as related to Adam their head and first father is the condition not only of inability,[15] not only the condition of no merit, but it is the condition of being damn worthy—worthy of damnation. All have sinned—all are worthy of, all deserve, all have merited damnation. There is no escape from this damnable condition; there is no remedy for the penalty earned through sin, original and actual. No act of a sinner will merit a removal of this penalty—even its temporal curses; no deed of a sinner will be the ground of remitting this sentence—even its temporal curses; no righteousness of a sinner will earn God’s payment of “no condemnation”—even its temporal curses. Only an act of grace; only an undeserved favor of God; only an act not arising from sinful demerit, sinful unrighteousness, sinful damnableness—only an act of God is able to remove the sinner’s penalty, to remit the sinner’s condemnation. Listen to Augustine: “grace bestows an undeserved honor, not for any privilege or merit” (Letter 194 To Sixtus). And Calvin: “. . . God is led by only one consideration. This is his own free goodness without respect for any merit at all, since in fact they can have no merit, either in their works or in their wills or even in their thoughts” (BLW, 136).

Augustine’s doctrine of grace emerges from his penetrating understanding of Paul’s doctrine of grace: “to the one who works, his wage is not reckoned as a favor but as what is due. But to the one who does not work, but believes . . . God imputes righteousness apart from works” (Rom. 4:4-6). The Augustinian antithesis is the Pauline antithesis: not human merit, human working, human earning, human deserving whether typological or eschatological, but God’s grace, God’s imputing, God’s justifying, God’s acting. “By grace are you saved . . . and that not of yourselves, it is a gift of God. Not of works lest any one should boast” (Eph. 2:8-9). The Augustinian antithesis is the Pauline antithesis: not yourself, not your works, not your deeds, not your obedience whether typological or eschatological, but grace, grace, God’s grace, God’s gift, God’s work, God’s doing, never yours ever.

Grace was not the place to begin for Pelagius, nor for his allies ever since. Pelagius began from man fully able to earn, merit, deserve the temporal and eternal rewards of God. In his commentary on Rom. 9:15, in which Paul cites God to Moses—“I will have mercy on whom I have mercy and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion”—Pelagius writes: “This is correctly understood as follows: I will have mercy on him whom I have foreknown will be able to deserve compassion” (Commentary on Romans [1993] 117). The sinful one who “will be able to deserve”—to merit, to be worthy, to earn God’s compassion. Command what you will, O Lord (Pelagius says), I will perform it; I am able to do it; I am even able to deserve your favor by the merit of my doing what you ask. Since you tell me I ought to, I am able to. Ought means can and I preach a can do gospel. What is this insulting drivel about human inability, absolute necessity of divine grace. This language is an insult to man’s dignity, to his self-esteem, to his God-likeness. Do not demean me by theories of original sin, moral turpitude, necessity of supernatural grace. These are the foul broodings of a flawed and pessimistic human mind—a mind diseased with its own failures and inhibitions. That is not Christianity—Christianity is freedom and the exercise of human potential and the full enjoyment of pleasure.

But Augustine, standing on the apostle Paul and revealed Scripture, said, “Human merits . . . perished through Adam” (On the Predestination of the Saints, 15.31; NPNF1, 5:513). Please observe what Augustine says here: human merit vanished, disappeared, perished, existed no longer with Adam. After Adam, no human merit—not in Noah, not in Abraham, not in Moses, not in Israel, not in David, not in Paul, not in Augustine, not in Pelagius.[16] When Adam sinned, sinful man was able to do only one thing from then on—demerit. For Augustine as for Paul as for Scripture as interpreted from itself, there is no merit in sinners in any way in any form in any dimension in any arena in any era—there is NO merit for sinners after Adam. “We must not imagine any meriting or deserving in any mortal creature” (“Sermon 68 on Dt. 9:25-29,” The Sermons of John Calvin on Deuteronomy [1583/1987] 418). There is only God’s grace. Command what you will, O Lord. And by your grace, O Lord, give what you command.

In the history of redemption, there are only two persons who could ever merit God’s reward: Adam the first and Adam the last (prelapsarian protological Adam and postlapsarian eschatological Adam). Only Adam and Jesus Christ were capable of merit—of earning the reward of God’s favor. No one between Adam and Christ or after Christ to his return has ever been able to merit anything from God except judgment and damnation whether typological or eschatological. Between Genesis 3 and the Second Coming, nothing but demerit for the sons of Adam and daughters of Eve. No one born by ordinary generation between Adam and Moses, between Moses and the parousia—no one has ever merited anything but cursing because every one from Adam to Moses and from Moses to the parousia is dead in trespasses and sin. And dead men merit nothing but death.

Here is what Augustine, Calvin, the Puritans and all other orthodox Reformed theology has understood: the God who lays down the condition is the God who performs the condition. This is true even with regard to Lev. 18:5, a central text to which our authors appeal to support their understanding of the works-merit paradigm in the Mosaic covenant (pp. 17, 19, 21, 109-18, 120-21, etc.). Clearly, Calvin’s interpretation differs from theirs.

[I]t is written, he that does these things shall live in them (Lev. 18:5; Rom. 10:5). Now then (says Saint Paul) let every man look into himself and examine his whole life: is there any man that is able to vaunt that he has fulfilled God’s law? No, we are all disobedient. Seeing the case stands so, there is no more life in the law: but we must rather flee to the free forgiveness of sins and especially beseech God to give us power to do that which we cannot. And so whereas the Papists do make themselves drunken with their devilish imaginations of meritorious works and such other like things: let us understand that after our Lord has allured us by gentleness, he adds a second grace: which is, that albeit we are not able to perform his commandments thoroughly in all respects, yet he bears with us as a father bears with his children, and imputes not our sins unto us… (John Calvin, “Sermon 19 [Dt. 4:1-2],” The Sermons of John Calvin on Deuteronomy [1583/1987] 112-13).

“Do this and thou shalt live”—the God who makes the condition must perform the condition; hence all notion of merit is nonsense, the product of, to quote Calvin, “woodenheaded pettifoggers”.

This is also the way Calvin interprets Deut. 30 (and related passages), another text appealed to by our authors in support of their construction of the distinctive features of the Mosaic and New covenants (pp. 122-29, 132-37). Consider how Calvin interprets this passage in terms of the Mosaic covenant.

True it is that here Moses exhorts the Jews to circumcise their hearts: but yet we shall see hereafter, how he will say, the Lord our God will circumcise your hearts (Dt. 30:6), it may well seem at the first sight that these two things stand not well together, but that there is some contrariety in them: and yet they agree both together very well. For (as I have touched before) it is our duty to be circumcised; that is to say, to cut off all that is of our own nature, and to rid it quite away that God may reign in us. But do we discharge ourselves thereof? No: but God must be fain to supply our want. And therefore it is he that circumcises us. Why then does he command us to do it, seeing we have neither power nor ability to do it? It is to the end that we should be sorry at the sight of our own wretchedness, and that seeing we fail and are so blameworthy, we should on the other side resort unto our God condemning ourselves, and on the other side be encouraged to desire him to do that which we ourselves cannot. . . But yet by the way we must understand that this serves not to magnify our own free will as the Papists have imagined. We have shown already that we are so little able by nature to come unto God that we draw clean back from him. Nevertheless to the intent to show us plainly what out duty is, he says unto us, do it: and although we are not able to set hand to the work, no, not to put forth a finger towards it; yet does he command us to do our duty, notwithstanding that we are utterly unable by any means to perform it. And that is to the end that we seeing our default, should be the more ashamed of it, and humble ourselves before God, and again that we should be provoked to pray him to work in us, seeing it is he that does all in us, notwithstanding that it is his will that we should be instruments of the power of his Holy Spirit. For as he is so gracious unto us as to impute his own doings unto us and to make us partakers of them: so also it is his will that we should acknowledge and take them for our own (“Sermon 72 [Dt. 10:15-17],” The Sermons of John Calvin on Deuteronomy [1583/1987] 441-42).

Calvin interprets the conditionality of the Mosaic covenant in terms of the Augustinian paradigm. God, who demands the condition, must supply the grace to fulfill the condition. He commands us to perform the condition that we might further see our need for grace—that we might cast ourselves upon him and his unmerited mercy so as to supply what is necessary for us to obey him.

This is not only how Reformed Augustinians interpret the conditional obedience required in the Mosaic covenant, it is also how Reformed Augustinians interpret the conditional obedience required in the new covenant: “Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ and thou shalt be saved”—the God who makes the condition must perform the condition; hence any notion of human ability to act on the condition, apart from the regenerating grace of God, is nonsense or Pelagianism masking as Reformed theology. This is the fundamental Pauline-Augustinian-Calvinistic-Reformed doctrine that so many do not understand today. They reason like Pelagius who see divine mandates and consequent promises of blessing for meritorious obedience. They suggest that demand of the condition augurs an ability in the sinners obliged to perform the condition; and having performed the condition, to merit or earn blessings on the ground of their obedience. We remind our readers once more of the statement on page 136: Israel’s obedience “would be the meritorious ground for Israel’s continuance in the land, the typological kingdom.”

This is unwitting Pelagianism (calling it “typological” does not alter its essential and substantial character) and Augustinian Calvinists are correct to see it as a threat to sola gratia as Augustine saw it 1600 years ago. It is for this reason that the favorite church father of Calvin, Vermigli, Bullinger, the Puritans, Edwards, Hodge, Gerstner, Van Til was Augustine. For Augustine saw—saw clearly that if it is by human merit then it is not by grace. And if it is by grace and not ever by human merit, then it is because the Lord God who demands the condition of performance of his will also graciously performs the condition of that demand in the lives of the sons and daughters of his grace. “It is by grace that any one is a doer of the law” (Augustine, Grace and Free Will, 12.24 [NPNF1, 5:454]). “The merit of our sins, of course, is not reward, but punishment” (Augustine, “Sermon 293,” New City edition, p. 152). In other words, if you claim human merit, you are demanding not blessing but cursing—for that is all a sinful member of the race of Adam can ever earn whether typological or eschatological. For what do you have that you have not received?! “The Israelites dared to glory . . . in meritorious works [but] grace is not given as a due reward for good works. Works do not precede grace but follow from it” (Augustine, “Letter to Simplicianus,” Part B, 2 [LCC, 386]). Grace is “made void if it is not freely given but awarded to merit” (“Letter to Sixtus”). “What God promises, no one but God performs” (ibid.).

But what of the rewards of the blessed about which the Scriptures speak? Augustine writes: “It is his own gift that God crowns, not your merits” (On Grace and Free Will, 6.15 [NPNF1, 5:450]). Not only is the performance of the condition of grace alone; any reward granted by grace to the performer is also graciously given, not meritoriously earned or deserved. The rewards described in Scripture are rewards of grace, gratuitous blessings, not meritorious performances. Remember, the absolute antithesis between grace and merit in Augustine, Calvin, the Reformed tradition, and above all Scripture: “But if it is by grace, it is no longer on the basis of works, otherwise grace is no longer grace” (Rom. 11:6).

What emerges from Augustine’s battle with Pelagius and the Pelagians is a ringing biblical definition of God’s grace. Grace is a free, unmerited gift of God. It is free, that is, sovereignly dispensed. It is unmerited, that is no recipient is worthy of it nor can they perform any act deserving of it; it is a gift—what do you have that you have not received as a gift. Its source is God alone, no other. That Augustinian biblical notion of grace is the very antithesis of merit.

Hence, the precise state of the question is this: whether merit exists or is even possible for or in any sinner or body of sinners at any point after the Fall? The orthodox say “No” against the Roman Catholics and all other merit mongers.

No merit at all, at any time in the history of redemption, whether for eschatological, typological or purely temporal rewards. None period. Thus Augustine on Paul and the Scriptures. And after him, Calvin and the Reformed tradition. Thus merit and grace in orthodox perspective—a perspective that, at best, is substantially modified and even obscured in the formulations of this book regarding Israel’s obedience in the Mosaic covenant. The “elephant in the room” controls this book.

This book is clearly an attempt to respond to criticism. The fact that it begins with a six-page fictional account of an ordination exam in which a candidate articulates views similar to those described in this book makes this fairly clear. The editors’ defensive posture is also evident in the following quote.

Recent evidence of this agitation in the church and elsewhere can be seen in the fact that the notion that Sinai republished a works principle has received much hostility in books, peer-reviewed journals, and trials in the courts of the church. Some are even calling for formal judicial discipline of ministers who hold to any view of the Sinaitic covenant that smacks of works being in place for pedagogical and typological purposes (17).

No specific examples of such hostility and criticism are cited by the authors. What exactly are they talking about? Where does such a view come from, and when did it first start receiving this kind of criticism?

Various answers can be given to this question, but in terms of the present debate, such criticism first arose in the early 2000s, especially in Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC). The most important example, in our opinion, was the 2003 trial of the Rev. Lee Irons, who was convicted of doctrinal error in the OPC for his views regarding the moral law, which were related to his views of the Mosaic covenant as a republication of the covenant of works. At that General Assembly trial, as well as the trial in the Presbytery of Southern California that preceded it, a number of the authors of this volume either defended Irons from the floor, voted against his conviction, and/or signed a protest against the General Assembly’s decision: J. V. Fesko, T. David Gordon, Bryan Estelle, S. M. Baugh, and Brenton Ferry. The names should be familiar to readers of this volume: they constitute nearly half of the authors in the volume under review. This (in itself) does not mean that they agreed with everything that Irons taught, but it does mean that they viewed him as being orthodox and within the bounds of the Reformed faith as summarized in the Westminster Standards (the doctrinal standards of the OPC). Clearly the Irons trial and its aftermath has put some of them on the defensive. Since the highest judicatory in the OPC found the views that they defended outside the bounds of Reformed orthodoxy, there is a danger that their own views may receive a similar evaluation as well.

It is also important to point out that the thesis of this book is essentially the same as that of Lee Irons defending himself in his 2003 OPC trial. The record of his defense shows that he argued (with reference to the WCF and the Reformed tradition in general) that “the Mosaic Law was thus understood to be in some sense a covenant of works.”[17] Notice how the language that Irons uses is identical to that of this book: the Mosaic covenant is “in some sense” a covenant of works. There are other parallels between Irons defense and arguments in this book, which we cannot detail here. The important thing to note at this point is that the catalyst for the present hostility to the views expressed in this book is the 2003 trial of Lee Irons. Though the authors of the book don’t tell you this, this is likely one of the chief reasons (though perhaps not the only reason) it is being written.

The connection between this book and the Irons trial should be clear. Not only did many of these authors defend Irons, they also articulate historical and exegetical points that are essentially identical with his.

It is true that in the Irons trial, the charges and specifications of error did not deal explicitly with the idea of the Mosaic covenant as a covenant of works.[18] But as we have shown, this idea was a central (if not the central) basis upon which the Irons position on the Decalogue was formulated. As Irons himself argued:

It is true that I teach that “the Decalogue is no longer binding on believers as the standard of holy living.” My reason for taking this position is, in a nutshell:

- There is a close relationship between the Decalogue and the Mosaic covenant as a whole. The Decalogue is called “the tablets of the covenant”…the Decalogue contains a summary of the moral will of God enshrined in a particular covenantal form suited to Israel’s probation in the land of Canaan.

- The Mosaic covenant is a typological republication of the covenant of works. The works-principle that informs the Mosaic covenant as a whole is evident in the Decalogue itself…[19]

Note well: one of the “reasons” for Irons “taking this position” that “the Decalogue is no longer binding on believers as a standard of holy living” is the fact that “the Mosaic covenant is a typological republication of the covenant of works.” In the mind of Irons, his teaching that the Mosaic covenant was a republication of the covenant of works, and his teaching that the Decalogue is no longer a standard of holy living are inextricably linked. The one serves as the “reason” for the other.

It is perhaps true that some of these authors might deny the connection that Irons maintains. They might hold to the “republication” view he describes and still affirm the abiding binding authority of the Decalogue. But this does not appear to be true of all of them. David VanDrunen’s essay formulates the doctrine of the Mosaic covenant that is very similar to Irons. In fact, he almost seems to suggest that the believer is no longer under the natural or Mosaic law “in regard to their conduct with one another” (although he insists that their basic moral obligations remain the same).[20] Moreover, T. David Gordon, in his public defense of Irons at the OPC General Assembly expressed his essential agreement with his position.[21] Whatever the fine points of distinction between Irons the authors in our present volume, it is still true that the Irons trial is an important element in the background behind this book. As noted above, their basic thesis on the issue is the same: the Mosaic covenant is “in some sense” a republication of the covenant of works. When Irons was convicted by the OPC General Assembly, it is no surprise that these supporters of his might be concerned that a similar judgment might be rendered on their views as well.

Since the Irons trial, debate and discussion over the republication issue has continued from a variety of voices. Perhaps the most noteworthy has been D. Patrick Ramsey’s article in Westminster Theological Journal (66:2 [2004] 373-400) entitled, “In Defense of Moses: A Confessional Critique of Kline and Karlberg.” Ramsey argues that Kline and Karlberg contradict the Westminster Confession in their mature teaching regarding the republication of the covenant of works in the time of Moses. His key historical-theological argument is that Kline and Karlberg articulate a position that is essentially identical to the “subservient covenant” view of John Cameron, Moise Amyraut, and the later “Amyraldians”—a view he maintains was explicitly rejected by the Standards.

A few months later, a response was written by Brenton Ferry, one of the contributors to this present volume, entitled “Cross-Examining Moses’s Defense” (67:1 [2005] 163-68). In it, Ferry defends Kline and Karlberg, arguing that they are not guilty of contradicting the Westminster Confession. Ferry’s key point is that in the 1968 publication, By Oath Consigned, Kline argues that the Mosaic covenant is renewed in the new covenant. As Kline writes:

Hence, for Jeremiah, the New Covenant, though it could be sharply contrasted with the Old (v. 32), was nevertheless a renewal of the Mosaic Covenant.[22]

Thus Kline is vindicated from the charge of teaching an “Amyraldian” view of the covenant.

The problem with Ferry’s argument is that what Kline taught in 1968 is not what Kline taught twenty, or thirty, or fourty years later. No less than Mark Karlberg himself (whom Ferry proposed to defend in his WTJ article) has critiqued Ferry for his failure to recognize this point.

And with respect to the Westminster controversy in particular, [Ferry’s] failure to acknowledge change and development in Kline’s thinking on the covenants only distorts an accurate reading of the history of Reformed interpretation, past and present.[23]

Karlberg points to an important principle in reading Kline’s works: the later works correct and revise the earlier works. Kline’s student, Lee Irons, has also noted this important principle, arguing that Kline’s position on the relationship between the Mosaic Covenant and the new covenant in By Oath Consigned is revised in his later work, Kingdom Prologue. Irons argues:

In other words, in KP [Kingdom Prologue] he no longer defines the New Covenant as a renewal of the Old/Mosaic Covenant (i.e., as a law covenant) and instead stresses the contrast between the Old and the New Covenants. The Mosaic Covenant was a covenant of works and was breakable. The New Covenant is a covenant of grace and is fundamentally unbreakable (although the sense in which it is unbreakable must be carefully defined).[24]

In other words, in Kingdom Prologue, Kline revises the position he articulated in By Oath Consigned, by arguing that “The New Covenant is not a renewal of the Mosaic Covenant but the fulfillment of the Abrahamic Covenant.”[25]

But Ferry ignores this development, and (in Karlberg’s words), “distorts an accurate reading of the history of Reformed interpretation, past and present.”[26] In fact, prior to the publication of Ramsey’s article, Lee Irons had argued (both in his General Assembly defense and on his weblog) that the “subservient covenant” view of Amyraldianism does in fact provide the best precursor of the mature Kline’s position on the Mosaic covenant. Irons argued that the Amyraldian “Subservient Covenant” is “A 17th Century Precursor of Meredith Kline’s View of the Mosaic Covenant.”[27] In this respect, Irons argues that “Kline’s understanding of the Mosaic Covenant has significant links with 17th century developments in covenant theology.”[28]

This is exactly what Ramsey argued in his WTJ article. In other words, when Kline’s mature view on the Mosaic covenant is precisely articulated, both friend and foe alike have argued that it bears striking and substantial similarities to the Amyraldian view of the Mosaic covenant. The only difference is that the “friends” have argued this to support Kline’s version of the “republication” thesis, while his “foes” have used it to critique it in terms of its confessional fidelity. We will discuss the Amyraldian view of republication below.

Richard B. Gaffin Jr. has also raised some concerns about the “republication thesis.” In a recent review of Michael Horton’s Covenant and Salvation, Gaffin expressed his concern regarding

Horton’s view that under the Mosaic economy the judicial role of the law in the life of God’s people functioned, at the typological level, for inheritance by works (as the covenant of works reintroduced) in antithesis to grace.[29]

Furthermore, Gaffin sees this position as creating “an uneasy tension, if not polarization, in the lives of his people between grace/faith and (good) works/obedience (ordo salutis), especially under the Mosaic economy.”[30] Gaffin’s comments do not directly address the relationship of Horton’s views to the Westminster Confession and the Reformed tradition in general, but they do express his general concern regarding not only the internal consistency of the position, but also how it may detract from an accurate reading of the Old Testament.[31]

Many other discussions have taken place regarding this issue. Some can be found on various blogs and internet discussion groups, often between ministers and elders in NAPARC denominations. As the editors note in their introduction to this volume, it has also become a point of contention in licensure and ordination examinations. Indeed, it is clear that this book is meant to function, in part, as a response to the concerned pastors and elders who appeared in fictional form in the introduction to this volume. Alternatively, this review should be read as an attempt to vindicate their concerns, and encourage them to continue asking precise and probing questions on this matter.

At the outset, we must reflect more directly on some problems related to the thesis of this book, namely, that the Mosaic covenant is “in some sense” a republication of the covenant of works. The problem, of course, is that this kind of thesis provokes an obvious question: in what precise sense is it a covenant of works? The thesis seems to be deliberately formulated to encompass a wide variety of views, as the authors of this book admit (20).

In our opinion, this imprecision creates a number of logical and theological problems with several of the positions propounded in the book. These particular problems are not necessarily exegetical or historical-theological, but are rather a matter of logical self-consistency. In other words, on careful analysis, several of the positions advanced in this book either fail to make logical sense, or utilize theological language in such an imprecise manner that they no longer carry their fixed theological meaning.

In order to make this clear, it is important to clearly define our terms. These authors maintain that the Mosaic covenant is “in some sense” a republication of the covenant of works. What precisely, then, is the covenant of works? The Westminster Confession of Faith makes this clear in at least two places:

WCF 7:2: The first covenant made with man was a covenant of works, wherein life was promised to Adam; and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience.

WCF 19:1: God gave to Adam a law, as a covenant of works, by which He bound him and all his posterity, to personal, entire, exact, and perpetual obedience, promised life upon the fulfilling, and threatened death upon the breach of it, and endued him with power and ability to keep it.

These two statements clearly articulate an essential aspect of the covenant of works, namely, that it requires perfect, personal, entire, exact, and perpetual obedience. We call this an “essential aspect” of the covenant of works because this requirement is absolutely necessary to a covenant of works. Put negatively, without the requirement for perfect, personal, entire, exact, and perpetual obedience, a covenant then ceases to be a covenant of works. In other words, we have only two options: either the covenant is a covenant of works, and requires perfect obedience, or the covenant is some other kind of covenant, and requires something other than perfect obedience (namely, the covenant of grace).

This is the fixed, accepted, confessional, and orthodox understanding of the covenant of works. So when we say that the Mosaic covenant is “in some sense” a republication of the covenant of works, then we are saying that the Mosaic covenant “in some sense” republishes the requirement for perfect, personal, entire, exact, and perpetual obedience. Is that what these authors mean when they speak of a “covenant of works” at Sinai?

The answer, for a number of them, seems to be a resounding “No.” We will focus on the position of two of the editors, Bryan Estelle and David VanDrunen. Estelle insists that the Mosaic covenant created a unique need for “sincere obedience, relative obedience (albeit) imperfect” (137). David VanDrunen also says that in the Mosaic covenant “God did not enforce the works principle strictly, and in fact taught his OT people something about the connection of obedience and blessing by giving them, at times, temporal reward for relative (imperfect) obedience” (301, n. 30). Estelle and VanDrunen are very clear: the Mosaic covenant did not actually require Israel to obey the law perfectly to receive the blessings of the land; rather he accepted their sincere, imperfect obedience.

At the same time, both of these authors insist (both in the Introduction and in their respective essays) that this arrangement should be referred to as a republication of the covenant of works. But as noted above, an essential component of the covenant of works is the requirement for perfect, personal, entire, exact, and perpetual obedience to the law. Without this requirement, the arrangement is not and cannot be a covenant of works. Rather it must be some other kind of covenant. To say that it only requires sincere, imperfect obedience, and at the same time call it a republication of the covenant of works (unless some distinct qualification or redefinition is given) is a logically incoherent statement. Unless, that is, we radically redefine the traditional signification of the term “covenant of works.” Much greater precision is demanded, particularly if progress is to be made on this knotty issue.

Now we must ask ourselves, in what kind of covenant does God accept sincere, imperfect obedience as a part of the requirements of the covenant? Clearly, it cannot be the covenant of works. A survey of a few prominent Reformed covenant theologians reveals that the only covenant in which imperfect, sincere obedience can be accepted as a condition of the covenant is the covenant of grace.

John Ball, a covenant theologian who was very influential on the Westminster Assembly,[32] described in detail the kind of obedience required in the covenant of grace:

Sincere, uniforme and constant, though imperfect in measure and degree, and this is so necessary, that without it there is no Salvation to be expected. The Covenant of Grace calleth for perfection, accepteth sincerity, God in mercy pardoning the imperfection of our best performances. If perfection was rigidly exacted, no flesh could be saved: if not at all commanded, imperfection should not be sin, nor perfection to be laboured after. The faith that is lively to imbrace mercy is ever conjoined with an unfained purpose to walke in all well pleasing, and the sincere performance of all holy obedience, as opportunity is offered, doth ever attend that faith, whereby we continually lay hold upon the promises once embraced. Actuall good works of all sorts (though not perfect in degree) are necessary to the continuance of actuall justification, because faith can no longer lay faithfull claime to the promises of life, then it doth virtually or actually leade us forward in the way of heaven [1 John 1:6-7]… (20-21).

Ball is clear: the covenant of grace accepts an obedience that is “uniforme and constant, though imperfect in measure and degree.” Indeed, it “calleth for perfection,” but “accepteth sincerity” through the forgiving grace of Christ. This kind of obedience is absolutely necessary for salvation, and is not in any way unique to the Mosaic covenant.

In another place, he expands upon this point and addresses the obedience of the Old Testament governors like Jehoshaphat, Josiah, Nehemiah and others. Ball argues:

Without question, they understood, that God of his free grace had promised to be their God, and of his undeserved and rich mercy would accept of their willing and sincere obedience, though weake and imperfect in degree; which is in effect, that the Covenant which God made with them and they renewed was a Covenant of grace and peace, the same for substance that is made with the faithfull in Christ in time of the Gospel (108).

Note the logic of Ball’s argument. Because the obedience conditioned in the Mosaic covenant was sincere, imperfect obedience, this covenant must therefore be a covenant of grace.

This is not just the view of Ball, but the testimony of the Reformed confessions of the 16th and 17th century. We will limit ourselves to three representative examples. First, the Scots Confession, chapter 15, says that in Christ, God “…accepts our imperfect obedience as if it were perfect, and covers our works, which are defiled with many stains, with the justice of his Son.” Second, chapter 16 of the Second Helvetic Confession teaches that:

…God gives a rich reward to those who do good works, according to that saying of the prophet…However, we do not ascribe this reward, which the Lord gives, to the merit of the man who receives it, but to the goodness, generosity and truthfulness of God who promises and gives it, and who, although he owes nothing to anyone, nevertheless promises that he will give a reward to his faithful worshippers… Moreover, in the works even of the saints there is much that is unworthy of God and very much that is imperfect. But because God receives into favor and embraces those who do works for Christ’s sake, he grants to them the promised reward.

Finally, the Westminster Confession teaches that although our works “…as they are wrought by us, they are defiled, and mixed with so much weakness and imperfection, that they cannot endure the severity of God’s judgment” (16:5), “Notwithstanding, the persons of believers being accepted through Christ, their good works also are accepted in Him; not as though they were in this life wholly unblamable and unreproveable in God’s sight; but that He, looking upon them in His Son, is pleased to accept and reward that which is sincere, although accompanied with many weaknesses and imperfections” (16:6). Clearly, since this is addressing the obedience and good works of believers in Christ, it is also addressing believers in the covenant of grace.

This is the uniform testimony of the Reformed confessions, which is confirmed by its explication in prominent Reformed covenant theologians. The specific nature of the obedience required/operative in the covenant of grace is that it is imperfect, although sincerely offered. It is only in a covenant of grace that such obedience can be accepted and rewarded by God, because it is only in such a covenant that the believer’s sins are covered and forgiven by the blood of Christ.

Yet the authors of this present volume insist that such obedience in the context of the Mosaic covenant functions in a way essentially different from the Abrahamic or new covenants. As Estelle put it, the new covenant has “essentially changed matters here” (136). Indeed, the editors together insist that “the covenant of works was republished at Sinai,” although not “as the covenant of works per se, but as part of the covenant of grace” (11). They then go on to insist (in the introduction) that this republication brought “the requirement for perfect obedience before the fallen creature, forcing him to turn to the only one who has been obedient” (11). In virtually the space of a few sentences, these writers (1) argue that the Mosaic covenant republishes the covenant of works, then (2) argue that it really wasn’t the covenant of works (because it didn’t require perfect obedience and functioned as part of the covenant of grace), and then (3) reverse themselves again and insist that in the Mosaic covenant the “requirement for perfect obedience” is brought before them, thus making it in some sense a true covenant of works. As we have shown, this same kind of inconsistency is evident throughout the argumentation of the book. Greater precision is necessary if we are to make sense of the specific proposals set forth in this book.[33]

So the reader (and the reviewer) is faced with a rather troublesome dilemma when seeking to evaluate their position. On the one hand, the authors use language that suggests that the Mosaic covenant is really a covenant of works that is actually applied to the life of Israel. But on the other hand, in their expositions they describe the unique obedience required in the republished “covenant of works” in a way that only makes sense if it is simply a covenant of grace (relative, sincere, imperfect obedience). To add more confusion into the mix, at times they also seem to indicate that the obedience required in the Mosaic covenant was indeed perfect obedience (not just imperfect and sincere). These formulations, without further nuance, qualification, or explanation, are mutually self-contradictory. They represent distinct positions that cannot logically coexist in the same manner in the same covenant arrangements.

Therefore, our authors are faced with a choice.[34] They must either discontinue their use of the language of “covenant of works” and “works principle,” to describe the Mosaic covenant, because it does not require perfect obedience. Or, they must alter their teaching that the Mosaic covenant actually did require perfect obedience, in which they can continue to accurately refer to it as a republished covenant of works. To call it a republication of the covenant of works, and insist that it only requires imperfect obedience is as confusing as that “black” is “white,” and “up” is “down.” They are mutually incompatible positions. Though we lay down this general criticism at the outset, we will return at times to it below.

The Law is Not of Faith begins with several historical articles. While D. G. Hart’s discussion of Old Princeton and the Law is worthy of comment, space requires that we limit our reflections to the heart of the debate about the historical-theological aspect of the book. Therefore, we will focus our attention on the contributions of J. V. Fesko and Brenton C. Ferry. These essays help set the tone for the entire article, as they seek to position the views of the authors within the mainstream development of Reformed theology from the 16th to 17th century. A careful analysis of them is therefore central to evaluating the views propounded in this book.

J. V. Fesko opens the volume with an analysis of John Calvin and Herman Witsius on the Mosaic covenant. In this chapter, Fesko aims to “take a comparative historical-theological snapshot of two continental Reformed theologians on this issue” (26). That is about as close as he comes to giving a clear thesis. It seems safe to assume, however, that the implicit thesis of the article, in keeping with the broader thesis of the book as a whole, is that both Calvin and Witsius believed that the Mosaic covenant was “in some sense” a covenant of works (6). It is in terms of Fesko’s contribution to this broader thesis that we will be examining his article below.[35]

Fesko begins by noting what has become a chief problem in many historical-theological treatments of this issue, particularly those of a more “Barthian” orientation. He states his hearty agreement with recent critiques of Barthian historians for being “more interested in vindicating their monocovenantal understanding of Scripture rather than doing accurate contextualized historical theology” (27). Well said. The problem (in our opinion) is that Fesko is guilty of the same error, only from another angle. In the final analysis, Fesko seems more interested in vindicating his own view of the Mosaic covenant than in doing “accurate contextualized historical theology.” It doesn’t matter whether this comes from a Barthian or a Klinean orientation: if you unwarrantedly see your own views in the men you are studying, you are committing the same error. We admit that Fesko is accurate in describing some aspects of Calvin and Witsius’s view (particularly their views concerning the substantial unity of the one covenant of grace). For this we give thanks to Fesko, and are grateful for his contribution. But in terms of the key issue set before us in the thesis of this book (that the Mosaic covenant is “in some sense” a covenant of works), Fesko’s treatment is flawed.

First of all, let us note how Fesko is guilty of anachronism in summarizing Calvin and Witsius on the Mosaic covenant. This is especially evident in the language Fesko uses to describe their views. He states that Calvin maintained that “the Mosaic administration of the law sets forth a principle of works” (30), and that “the Mosaic covenant was governed by a works principle” (32; cf. 33). This language of “works-principle” does not appear in Calvin. It does, however, figure prominently in his own view of the Mosaic covenant as well as that of Meredith G. Kline.[36] It makes sense that Fesko would use this language to describe Calvin’s view. It allows him to draw a direct (linguistic) line of connection between Kline and Calvin. Furthermore, he unhelpfully utilizes the terms historia salutis and ordo salutis in analyzing their theology. While these terms may serve a useful purpose, in our opinion, since the subject of his analysis is so hotly disputed, it would have been better for him to leave them to the side, and stick to the language indigenous to the 16th and 17th century.[37] As Fesko has pointed out, one must always be cautious of reading one’s own theological position back onto the writers you are analyzing. One way to guard against this is avoiding anachronistic language.

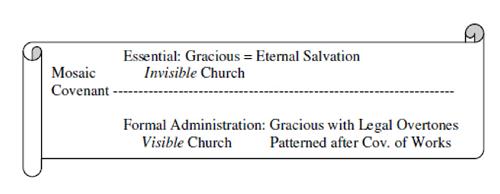

What then, does Fesko say is Calvin’s view of the Mosaic covenant? According to him, “Calvin explains that in the dispensation of the Mosaic covenant there are two separate covenants” (30). What evidence does Fesko provide to support this view? He appeals to Calvin’s linguistic distinction between a foedus legale and a foedus evangelicum, arguing that there is “a sense in which Calvin sees these two covenants in an antithetical relationship to one another” (30). The primary difference, for Fesko, is that the foedus legale “sets forth a covenant governed by a works principle, namely, eternal life through obedience” (30).

However, there is a problem with Fesko’s analysis. The terms foedus legale and foedus evangelicum are almost always (for Calvin) terms used to describe the various administrations of the covenant of grace, not a “separate covenant,” characterized by a “works principle” operative in the Mosaic administration. This is clearly the case in 2.11.4 of the Institutes (which Fesko cites to defend his analysis), where Calvin writes (commenting on Heb. 7-10):

Here we are to observe how the covenant of the law (legale) compares with the covenant of the gospel (evangelicum), the ministry of Christ with that of Moses. For if the comparison had reference to the substance of the promises, there would be great disagreement between the Testaments. But since the trend of argument leads us in another direction, we must follow it to find the truth.

For Calvin, the foedus legale and foedus evangelicum are not “two separate covenants” as Fesko states, but they are in fact two names for two different administrations of the same covenant. The comparison between the foedus legale and the foedus evangelicum does not refer to the “substance” of the covenants. Rather as Calvin goes on to explain in the same section, the two terms only refer to a twofold way of administering the same covenant:

Let us then set forth the covenant that he once established as eternal and never-perishing. Its fulfillment, by which it is finally confirmed and ratified, is Christ. While such confirmation was awaited, the Lord appointed, through Moses, ceremonies that were, so to speak, solemn symbols of that confirmation. A controversy arose over whether or not the ceremonies that had been ordained in the law ought to give way to Christ. Now these were only the accidental properties of the covenant, or additions and appendages, and in common parlance, accessories of it. Yet, because they were means of administering it, they bear the name “covenant,” just as is customary in the case of the other sacraments. To sum up, then, in this passage “Old Testament” means the solemn manner of confirming the covenant, comprised in ceremonies and sacrifices (2.11.4).

In 2.11.4, Calvin is not teaching that the Mosaic covenant should be viewed as a “separate covenant” governed by a works-principle. In fact, Calvin makes the opposite point in this very passage, namely, that the Mosaic covenant is essentially a covenant of grace, though differently administered.

Fesko also appeals to Calvin’s Institutes 2.11.7 to support his interpretation of the foedus legale. The reader should note the jump: the first quote comes from 2.11.4, while the second comes three sections later. The two are then woven together in a way that makes them appear like a seamless garment. But in 2.11.7, Calvin is not speaking of a “separate covenant” during the Mosaic administration, but rather of “the mere nature of the law” abstracted from that covenant. Calvin is analyzing the words of Hebrews and Jeremiah, whom he says “consider nothing in law, but what properly belongs to it.” As the very next section (2.11.8) clearly demonstrates, Calvin understands Jeremiah to be speaking simply of the moral law itself, not of a “separate covenant” operative in the Mosaic administration: “Indeed, Jeremiah even calls the moral law a weak and fragile covenant [Jer. 31:32].” In other words, Fesko’s error is that he applies what Calvin says about the moral law to a separate covenant in the Mosaic administration. This is very strange, considering that he himself had told us at the start of the article that—“When one explores Calvin’s understanding of the function of the law, he must therefore carefully distinguish whether he has the moral law or the law as the Mosaic covenant in mind” (28). Well said. But when it comes to one of the most crucial points in his reading of Calvin, he chooses to ignore that distinction and applies what Calvin says about the moral law to the Mosaic covenant itself.

The significance of this mistake cannot be underestimated. It is the only primary document evidence that Fesko gives to support this key aspect of his thesis. On page 33, he summarizes in six points his thesis regarding Calvin’s view of the Mosaic covenant. To points 1-4, we say “Amen.” But for the reasons outlined above we cannot agree with points 5-6.

(5) The Mosaic administration of the law is specifically a foedus legale in contrast to the foedus evangelicum, the respective ministries of Moses and Christ; and (6) the foedus legale is based upon a works principle but no one is able to fulfill its obligations except Christ (33).

What Fesko should have said is that for Calvin, the moral law, narrowly considered, promises eternal life for perfect obedience. To say that the “Mosaic covenant is characterized by a works principle” (32) is only to confuse what Calvin keeps clear. The moral law itself may promise life for perfect obedience, but Calvin does not speak this way about the Mosaic covenant or the foedus legale.

Now, we must ask the question, why does Calvin consider the law in this narrow sense? Is it because during the Mosaic administration there was a “separate covenant” that was governed by a principle of works (as Fesko states)? By no means. Calvin must be allowed to interpret Calvin. Why is it that Paul (and the other New Testament writers) sometimes speak of the law in this “narrow sense?” Calvin explains:

He was disputing with perverse teachers who pretended that we merit righteousness by the works of the law. Consequently, to refute their error he was sometimes compelled to take the bare law in a narrow sense, even though it was otherwise graced with the covenant of free adoption (2.7.2).

Note well: the law is taken in the narrow sense when Paul is refuting the Judaizers, who maintained that we “merit righteousness by works of the law.” He makes the same point in his commentary on Rom. 10:4.

The Apostle obviates here an objection which might have been made against him; for the Jews might have appeared to have kept the right way by depending on the righteousness of the law. It was necessary for him to disprove this false opinion; and this is what he does here. He shows that he is a false interpreter of the law, who seeks to be justified by his own works…It hence follows, that the wicked abuse of the law was justly reprehended in the Jews, who absurdly made an obstacle of that which was to be their help: nay, it appears that they had shamefully mutilated the law of God; for they rejected its soul, and seized on the dead body of the letter. For though the law promises reward to those who observe its righteousness, it yet substitutes, after having proved all guilty, another righteousness in Christ, which is not attained by works, but is received by faith as a free gift. Thus the righteousness of faith (as we have seen in the first chapter) receives a testimony from the law. We have then here a remarkable passage, which proves that the law in all its parts had a reference to Christ; and hence no one can rightly understand it, who does not continually level at this mark.

Note how Calvin interprets Paul on the law. He often takes the law “in a narrow sense” to refute “perverse teachers who pretended that we merit righteousness by works.” These Jews “rejected its [the Law’s] soul, and seized on the dead body of the letter,” and thus “shamefully mutilated the law of God.” Its true purpose was not only to promise “reward to those who observe its righteousness,” but also to substitute “after having proved all guilty, another righteousness in Christ, which his not attained by works, but received by faith.”

Cornel Venema has noted this important aspect of Calvin’s teaching on the “legal covenant.”

For Calvin, these legal promises were never intended to play an independent role with regard to the evangelical promises…That the apostle Paul or other biblical authors should ever speak of the law in this narrow sense, wrested from its evangelical setting, is only owing to the false claim of some that salvation can be gained through keeping the law.[38]

Though Venema includes a blurb on the back cover of the book under review “recommending” the volume, he also notes that “I am not persuaded by every formulation here.” This must have been one of the points of which he was not persuaded.[39]

In his clearest and most direct statements, Calvin affirms not only the essential continuity, but also the identity of the old and new covenants. Commenting on Jeremiah 31, Calvin writes:

Now, as to the new covenant, it is not so called, because it is contrary to the first covenant; for God is never inconsistent with himself, nor is he unlike himself, he then who once made a covenant with his chosen people, had not changed his purpose, as though he had forgotten his faithfulness. It then follows, that the first covenant was inviolable; besides, he had already made his covenant with Abraham, and the Law was a confirmation of that covenant. As then the Law depended on that covenant which God made with his servant Abraham, it follows that God could never have made a new, that is, a contrary or a different covenant…These things no doubt sufficiently shew that God has never made any other covenant than that which he made formerly with Abraham, and at length confirmed by the hand of Moses (emphasis ours).

Here Calvin explicitly rejects, in so many words, the very position Fesko imputes to him, namely, that Moses introduced a contrary, separate covenant in the life of the people of Israel. Compare again the two statements. Fesko says “Calvin explains that in the dispensation of the Mosaic covenant there are two separate covenants” which are in some sense in an “antithetical relationship to one another” (30). Calvin says that “God could never have made a new, that is, a contrary or a different covenant” with the people of Israel. God did not bring in anything substantially different through the Mosaic covenant; it was essentially the same as the Abrahamic: “God has never made any other covenant than that which he made formerly with Abraham, and at length confirmed by the hand of Moses.” How can this be true if Calvin teaches that the Mosaic covenant introduces a “separate covenant” governed by a “works principle” that is in an “antithetical relationship” to the Abrahamic covenant?

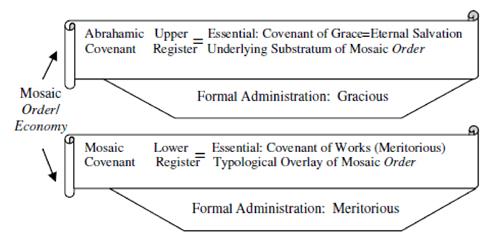

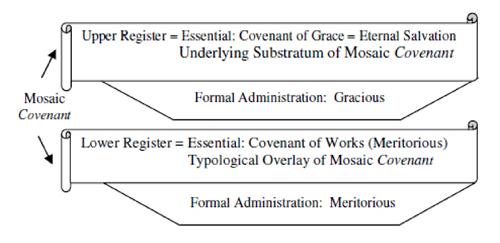

Fesko misinterprets and misrepresents Calvin’s position by suppressing the above-mentioned aspects of his teaching. In so doing, Fesko makes Calvin sound more like one of his (and the other authors) favorite contemporary covenant theologians: Meredith G. Kline. In fact, in our opinion, he appears to be doing nothing more than Mark Karlberg did before him: reading a form of Kline’s view onto Calvin.[40] Kline taught that in the Mosaic administration there were two separate covenants: one of works, and one of grace. The former was superimposed upon the underlying substratum of the Abrahamic covenant of grace. Again, Fesko’s interest in vindicating his own view (Kline’s) of the Mosaic covenant seems to have created a roadblock in his efforts for an “accurate contextualized historical theology.”

Interestingly, this same strand of Calvin’s teaching on the Mosaic covenant reappears in Herman Witsius.

Having premised these observations, I answer to the question. The covenant made with Israel at Mt. Sinai was not formally the covenant of works…However, the carnal Israelites, not adverting to God’s purpose or intention, as they ought, mistook the true meaning of that covenant, embraced it as a covenant of works, and by it sought for righteousness. Paul declares this [Witsius references both Rom. 9:31-23 and Gal. 4:24-25]…For in that place [Gal. 4:24-25] Paul does not consider the covenant of Mt. Sinai as it is in itself, and in the intention of God, offered to the elect, but as abused by carnal and hypocritical men (Witsius, 2:184-85).

Witsius then goes to quote Calvin from his commentary on Gal. 4:24.

Let Calvin again speak: “The apostle declares, that, by the children of Sinai, he meant hypocrites, persons who are at length cast out of the church of God, and disinherited. What therefore is that generation unto bondage, which he there speaks of? It is doubtless those, who basely abuse the law, and conceive nothing in it but what is servile. The pious fathers who lived under the Old Testament did not so. For the servile generation of the law did not hinder them from having the spiritual Jerusalem for their mother. But they, who stick to the bare law, and acknowledge not its pedagogy, by which they are brought to Christ, but rather make it an obstacle to their coming to him, these are Ishmaelites (for thus, and I think rightly Marlorat reads) born unto bondage.” The design of the Apostle, therefore, in that place, is not to teach us, that the covenant of Mount Sinai was nothing but a covenant of works, altogether opposite of the gospel-covenant; but only that the gross Israelites misunderstood the mind of God, and basely abused his covenant; and all such do, who seek for righteousness by the law (ibid.).

Witsius concludes by referencing Calvin again, from his commentary on Rom. 10:4, which we have provided above.

This aspect of Calvin and Witsius’s teaching is crucial for understanding their doctrine of the Mosaic covenant. Both Calvin and Witsius appeal to it lest the Scriptures be misunderstood as teaching that the Mosaic covenant was (as Witsius puts it) “nothing but a covenant of works, altogether opposite of the gospel-covenant.” Yet Fesko only briefly mentions, in truncated form, this aspect of their teaching on the Mosaic covenant, and does not let it substantially affect his analysis.[41] Why? He has obviously read through these sections of their works. Is it because it doesn’t fit his polemical agenda? Fesko, as with many of the other authors in this book, seems more interested in legitimizing some form of the views of Meredith G. Kline, rather than doing “accurate, contextualized historical theology.”

Let us now turn our attention directly to Fesko’s analysis of Witsius on the Mosaic covenant. Before we begin our analysis of Fesko’s treatment, it will be good for us to set Witsius in his historical-theological context. McClintock and Strong say this about him.

The principal work of Witsius…was published in 1677, and originated in his desire to meliorate the acrimonious spirit apparent in the controversies between the orthodox and the Federalists. His plan involved no true mediation between the opposing systems, however, but merely the knocking-off of a few of the more prominent angles on the Federal hypothesis; and he succeeded only in raising a storm among the Federalists against himself, without conciliating the opposing party.